The rise of parasocial relationships in the Internet age

The advent of broadcast media in the 19th century expanded the human experience – with radio and television providing new ways for people to connect and feel connected.

It also marked the emergence of ‘parasocial relationships’, a term coined by sociologists Donald Horton and Richard Wohl in 1956. Traditionally relationships are marked by a mutual sharing of energy and care between two people. In contrast a parasocial relationship is a one-sided affair, where “viewers or listeners come to consider media personalities as friends, despite having limited interactions with them.”

The introduction of digital media and social media has only seen this phenomenon grow – with the rise of sites like YouTube and Instagram paving the way for ‘influencers’ to build their fan bases with carefully curated online personas. Aspects of these sites have been meticulously engineered with the aim to foster parasocial relationships – with fans choosing to ‘follow’ or ‘subscribe’ to their favourite personalities, who interact with their followers as if around an intimate dinner table.

Some theorists even suspect that parasocial relationships were a driving force behind a certain orange-faced reality show celebrity come American president’s popularity at the voting polls (Gabriel et al. 2018).

Professor Ofir Turel, Professor at the School of Computing and Information Systems, The University of Melbourne and Scholar in Residence, Decision Neuroscience Program, University of Southern California, says that social media has provided greater access to online personalities, while also giving the illusion of intimate connection.

“Everything is accentuated online because now you have access to a much larger group of people. One basis for creating connections with friends is them revealing private information to you, and with social media, pretty much everybody is revealing private information. So, it’s easy to believe that a person is telling just you about their life, not their 8 million other followers. It’s easy then to feel you have a special sort of a connection with this person.”

Like all online interactions, parasocial relationships can provide both positive and negative effects for those engaging in this behaviour. On the one hand, parasocial connections can supplement filling social needs, and decreasing loneliness for people who struggle to make real world connections (a need that intensified due to the roll-on effects of COVID-19).

“Parasocial relationships at their heart are not necessarily dangerous. It can be healthy and provide people with some meaning in life – substituting the need to connect and socialise in cases where that has been restricted,” says Professor Turel.

But on the other hand, they can be the source of feelings of inferiority, create a false sense of reality, contribute to obsessive online behaviours and withdrawal from real life friendships.

“People need to be aware of that. It’s like any other interaction. They could be taken advantage of if they’re not mindful that this person is not actually their friend. They do not have their best interest in mind.”

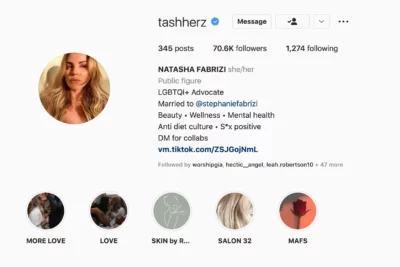

Natasha Fabrizi (nee Herz) was first thrust into the world of parasocial relationships after starring as one half of the first lesbian couple on the 2020 series of Married at First Sight (Australia).

Overnight her social following jumped from a few thousand to over 70K, and with it came a slew of people that felt a genuine connection with her.

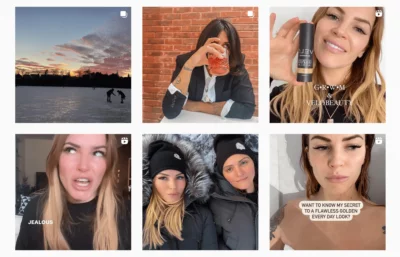

Natasha, who is now a health and beauty influencer, says that the experience has been a learning curve in how much energy she invests in engaging with her followers.

“It’s about the fact that they’re strangers and you are giving them these valuable energy deposits. Especially as an introvert, because it’s rare that I glean a lot of energy from lots of social interaction. So, once I put my energy somewhere, it definitely takes a toll on me and drains me,” says Fabrizi.

“At the start I felt such pressure, it felt like it was my role to help these people because they were coming to me and sharing and being so vulnerable. I used to kill myself, writing big emotional responses to people. And then I learned not to.”

With the added pressure of being a visible LGBTQIA+ persona, Natasha says that through a process of trial and error, she has had to create a set of rules for herself around what she will and won’t offer online.

“People feel like they are owed your attention because you have a platform. They will ask you to share things. And if you don’t want to, they think that you are just being mean or dismissing them. They don’t understand that if you’re making money from your platform, then you have to curate it in a specific way,” says Fabrizi.

“As a rule, I don’t share GoFundMe pages, because I’m never a hundred percent on whether they’re legitimate or not.”

The entitled dynamic between follower and followed gets more complicated when information emerges that contradicts who they thought they were following. This became particularly evident in the very public defamation case between Johnny Depp and his ex-wife Amber Heard.

Despite witness testimony, recordings of Johnny Depp in drunken rages, and a successful court case against him in the UK, Depp’s fan base launched a coordinated attack on his ex – questioning the sincerity of her claims, as well as her validity as a victim of domestic violence.

Professor Turel puts this down to cognitive dissonance – the “state of having inconsistent thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes, especially as relating to behavioural decisions and attitude change.”

“If you have a certain perception about Johnny, that he is just this funny character, and then suddenly you are presented with another perspective on him that doesn’t align with this – people will want to ignore this information because it’s very discomforting,” says Professor Turel.

“It’s uncomfortable to have this notion that your favourite character is behaving in a way that is inconsistent with the way you view him.”

Despite the threat of a backlash, Natasha says that she still feels that part of her role as a visible persona is to be vocal about issues that mean something to her.

“You do have a certain duty to be a good example. When I first came off the show (MAFS) and I had a lot more engagement, I wasn’t thinking things through and venting and being very emotional on that platform (Instagram). And it can get messy and cause you drama,” says Fabrizi.

“However, if it’s a public person and it’s something that I greatly disagree with, I will speak up about it. And it’s partly because it’s a smart thing to do engagement wise. And obviously partly because I’ve felt moved enough to talk about it publicly.”

And while as a society we will continue to grabble with what parasocial relationships say about us as humans, Professor Turel is erring on the side of optimism.

“Even though we are faced with increasing challenges with social media, I tend to be optimistic about humanity. We have had these issues for ages, and we are getting better at understanding them and taking control over our behaviours,” says Professor Turel.