Influencer burnout is a harsh reality in an unreal world

Influencer. It’s a word that can elicit a range of responses depending on your individual standpoint. But regardless of your outlook, it’s a job title that continues to entice hordes of young people. Yet increasingly those that have found success via this unconventional career are logging off or ‘going dark’.

Changes in algorithm and the push to create constantly to stay relevant, bullying and harassment from followers, and the volatility inherit in this type of ephemeral role all contribute to a growing burnout that is leaving certain creators feeling tapped out, both emotionally and physically.

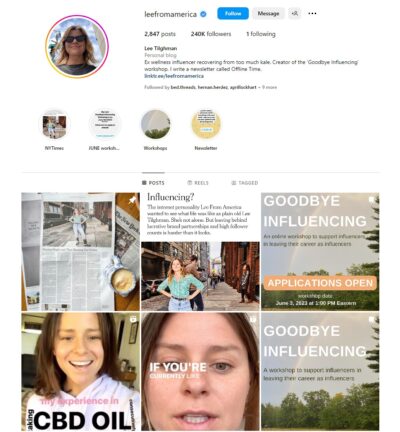

It has also sparked a counterculture movement of the anti-influencer, led by ex-wellness influencer Lee Tilghman (Lee from America) who now provides a ‘Goodbye Influencing Workshop’ that promises influencers, “stuck on the hamster wheel of content creation” a way out and provide insight and support to “help translate the skills you’ve built being an influencer and transform that into a completely new career.”

Lee’s about-face and exit strategy business acumen earned her a coveted profile in The New York Times, where she shared that, despite making as much as $20,000 for a single branded Instagram post in her heyday, she is much happier now.

She adds, “I’m in the world. I have deeper friendships. I have a bigger social life. I get to do the things I want to do.”

Of course, burnout isn’t a phenomenon unique to influencers and content creators, with nearly every industry coming up against widespread workforce fatigue since the advent of covid. But according to a report by venture firm SignalFire, more than 50 million people consider themselves creators (influencers, bloggers, videographers), making the content creator industry the fastest-growing small-business segment, owing in large part to the aforementioned pandemic.

In a survey conducted by Morning Consult in 2019 among Gen Z and Millennials in the US, 54% stated they would become an influencer, given the opportunity, and 86% said they would be willing to post sponsored content for money.

The allure of influencer status can be strong, especially for young people, but early adopters of the lifestyle are now finding that their online life is having lasting negative effects. One such creator is Youtuber Elle Mills, who started her journey as a vlogger at the ripe age of 12 years old, growing her audience to over 1.73 million subscribers before quitting at the age of 24.

In an op ed for The New York Times, Mills writes about growing up in the public eye and coming to the realisation that being an online persona was taking more away from her life than it was adding. She writes, “Part of the culture is to make yourself into a product and figure out how to sell that product. Success is measured in views and subscriber counts, visible to all. The numbers feel like an adrenaline shot to your self-esteem. The validation is an addicting high, but its lows hit just as hard.”

Mill’s concerns about balance are echoed by others working in the industry.

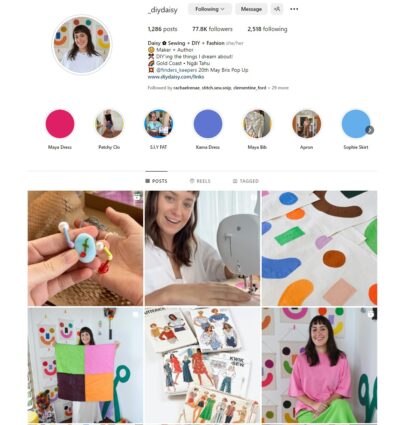

Boasting over 77.8K followers on her Instagram alone, self-proclaimed content creator (she doesn’t align with the influencer label) Daisy Baird started her journey as DIY Daisy in earnest after returning to Australia from Japan during the pandemic.

“I came back to Australia, and it was lockdown. I had a big pile of fabric and a lot of time. So, I thought, I’ve shared one or two (sewing) tutorials, maybe I’m going to try and do some more,” she says.

“It wasn’t until I hit 20,000 followers that my parents were like, ‘whoa, ok something is happening here’. That’s when I started getting brands reaching out to do collaborations.”

While Braid currently works part time as social media manager and part time on DIY Daisy, she says that the pressure of having to be constantly ‘on’ while in public does weigh on her.

“I’m very aware that I am a brand, and sometimes I don’t want to be. Sometimes I just want to wear a really daggy outfit and be a total, lazy lump when I go out,” Braid says.

“But if someone recognises me, I want to make sure that I look like DIY Daisy, that I’m representing myself as my brand.”

Baird says that at the height of her online presence (in the lead up to the launch of her book), she put her life and personal relationships on hold in order to sit in “hustle mode.” But she says that her focus now is about bringing more balance into her relationship with her online life and offscreen one.

“I’m constantly working towards a more balanced relationship with social media, and how I engage with it, not just for work, but also for myself. The long-term impacts, both physical and emotional are always front of mind. I already have RSI in my hands, and if I want to continue my craft, I need to take care of myself,” says Baird.

Which means sometimes turning her phone to silent.

“I hate notifications. It’s part of the job, but I really find them almost triggering, because I don’t want to be constantly online. I really love going offline now and going away for the weekend and just not looking at my phone.”