Is this the end of the arsehole era?

In order to ‘win’ in business or politics, traditionally many leaders have perceived the need to push the boundaries of ethics and what a ‘typical’ person would view as morally right.

This can mean that leaders, still often more so men than women, have removed ethics, and are willing to win at any cost, even if it means being a bit of an arse. Business can be tough and self preservation, and domination can supersede ethics and codes of conduct.

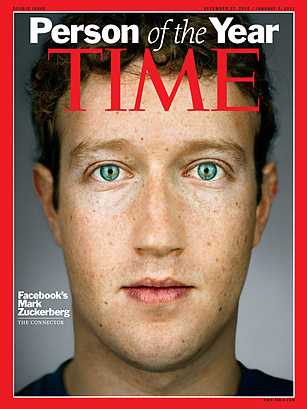

The likes of Facebook to Uber are well documented as profiting from being bad. Regulations in recent years, and negative media attention for those pushing ethical boundaries, has highlighted what good looks like. It is plausible that regulations force good behaviour.

Way back in 2019 I interviewed former MD of Facebook Australia and New Zealand. It was a fascinating interview about how the culture of Silicon Valley and the likes of Facebook thrive. What I found particularly interesting was the exploitation of the gap between ‘ethics’ and ‘regulations.’ This is that morally questionable zone where profit opportunity exists, as fast growth juggernauts exploit the gaps to make profit and other growth before the regulators catch up. Trying to be good, or at the very least, trying to be viewed as good, is much easier once your fundamental bad is highlighted to the community.

Stephen Scheeler – Silicon Valley, Visionary Leaders, Culture and Cults

Mark Zuckerberg Knows Exactly How Bad Facebook Is

49 of the biggest scandals in Uber’s history

Similarly, politics is also traditionally a nasty space. The aim to win at any cost, without breaking any regulations is a common strategy to optimise votes. As is the case with many questionable businesses, politicians can seek victory in exploiting the gap between ethics and rules.

A common political strategy is attempting to leverage the fear and insecurities of the community in order to entice voters. Exploiting the fears of voters towards change, longing for the ‘the good old days’ and ease of many to be influenced even with flimsy evidence.

Political strategists can attempt to leverage cognitive bias in voters to win elections.

Loss aversion is a cognitive bias that describes why, for individuals, the fear of losing is psychologically twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining. The loss felt from money, or any other valuable object, can feel worse than gaining that same thing. From a political sense, loss aversion may be anything from a loss of economic or job security, personal comforts or even a fear of losing the sense of old fashioned family or other values of old.

Social proof is the psychological tendency for people to seek conformity to ensure they behave in a socially acceptable manner. It makes people feel confident, a sense of belonging and sharing commonality. Norms can be set with very little information or actual evidence. Attitudes and behaviours are formed by what people believe to be true and pass on to others.

Just-world fallacy is the cognitive bias that assumes that “people get what they deserve.” For example, those struggling financially haven’t worked as hard as others. Or, a young girl sexually assaulted was to blame as she was pretty or must have put herself in the wrong situation. There can be a sense, particularly from older generations, that the world is fundamentally fair and the values of old are sufficient to protect ourselves and the community.

There is nothing new in politics and political advertising in attempting to manipulate voters. What’s interesting about the most recent election, is such manipulation actually seemed to largely fail. Unsuccessful political campaigns from Trump to the Morrison Government may illustrate that such negative campaigns create conflict fatigue amongst votes, and perhaps there’s a better way moving forward.

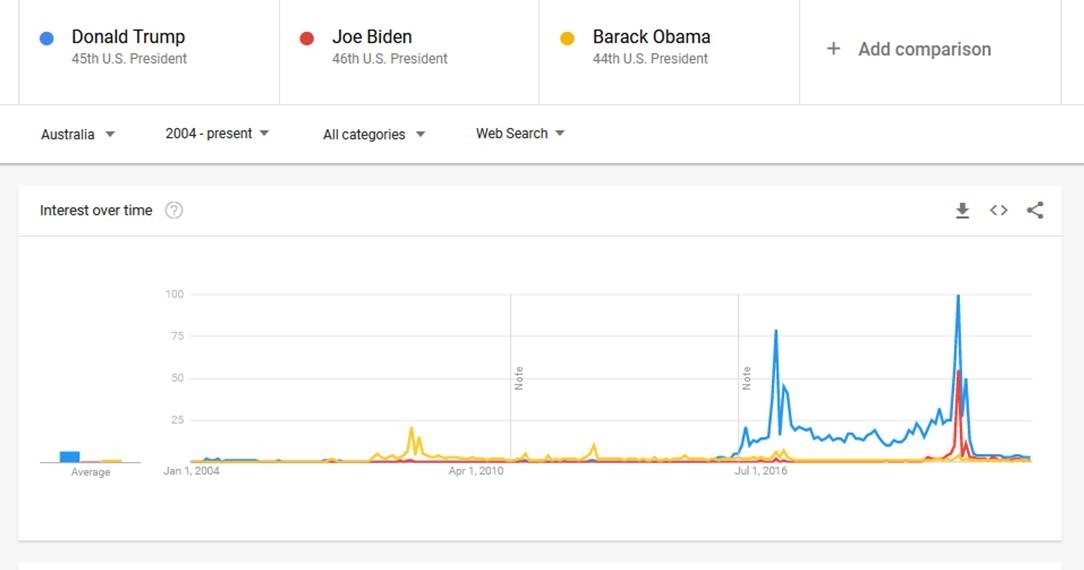

Trump clearly played an aggressive political game, and it is interesting to observe searches via Google illustrating his prominence over time compared with the US’s 46th and 44th Presidents. Trump’s abrasive campaign succeeded in building visibility if not reelection.

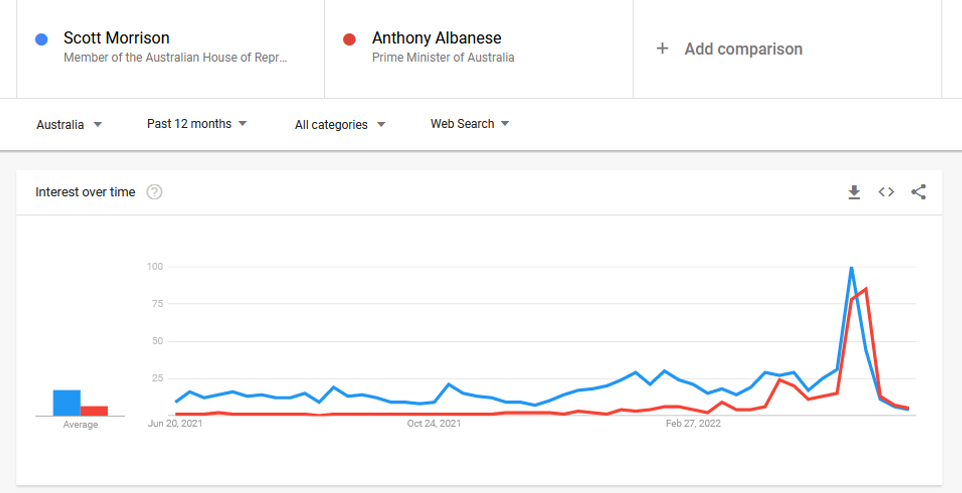

In Australia’s recent Federal election, The Scott Morrison Liberal Government also launched an aggressive campaign. Over the past 12 months, Morrison has notably had stronger visibility on Google than Albanese. Morrison won the visibility, not the election.

Success in marketing is often viewed as optimising visibility, yet commentators have criticised the tone of the 2022 political ads, claiming that voters are now wanting better.

Marketing experts deride ‘highly irritating’ political ads

Hole in your budget: is the most annoying ad of the election also the most effective?

Election campaigns are commonly negative, exploiting fear. It can feel like the political attacks will never end. Thankfully, as the election decision comes through, the loud angry voices can quickly quieten, as the aggressive leaders disappear from the media spotlight.

Despite all the bad news, the angry barking has slowed

What Ever Happened to Donald Trump?

What is interesting is that a negative campaign, while creating more visibility, thankfully does not guarantee an election win. Perhaps voters are now expecting more. Similarly, businesses are having regulations and clear guidelines of good versus bad, and hopefully with this unethical leaders will decline. It is overly idealistic that bad business and politics will disappear, but hopefully the fight of good versus evil is moving in the right direction.

The world is a much better place when the message grows that arseholes are not welcome.