The Toys That Bind Us: When Merchandising Comes First

Merchandising is big business these days, with an estimated 3 billion toys sold annually in the U.S., amassing an economic impact of $102.4 billion each year. Supported by the sheer number of superhero movies released over the last few years, it’s not hard to see why sales continue to rise. Yet, with the growing popularity of these films and the sheer dollar values they attract, many fear that the focus has moved away from the suit worn by the hero to the suit worn by the boardroom executive.

Toys in particular are an essential but often overlooked piece of the movie-making puzzle. With each new major superhero film to be released, movie studios grow cleverer in how they position and leverage their range of products. But as the dollar value of merchandising continues to increase, the question arises – to what extent does (or should) merchandising take precedence over the stories and characters they attempt to represent, in the name of sales?

Known as the process of ‘toyification’, where elements of a design are intentionally created to look or feel ‘toy-ish’, comic brands have long been positioning their media as over-grown toy commercials. Yet, comic-to-movie adaptations now service a wider audience than ever, and thus, the commercial element of such films (as merchandising opportunities) cannot be overstated.

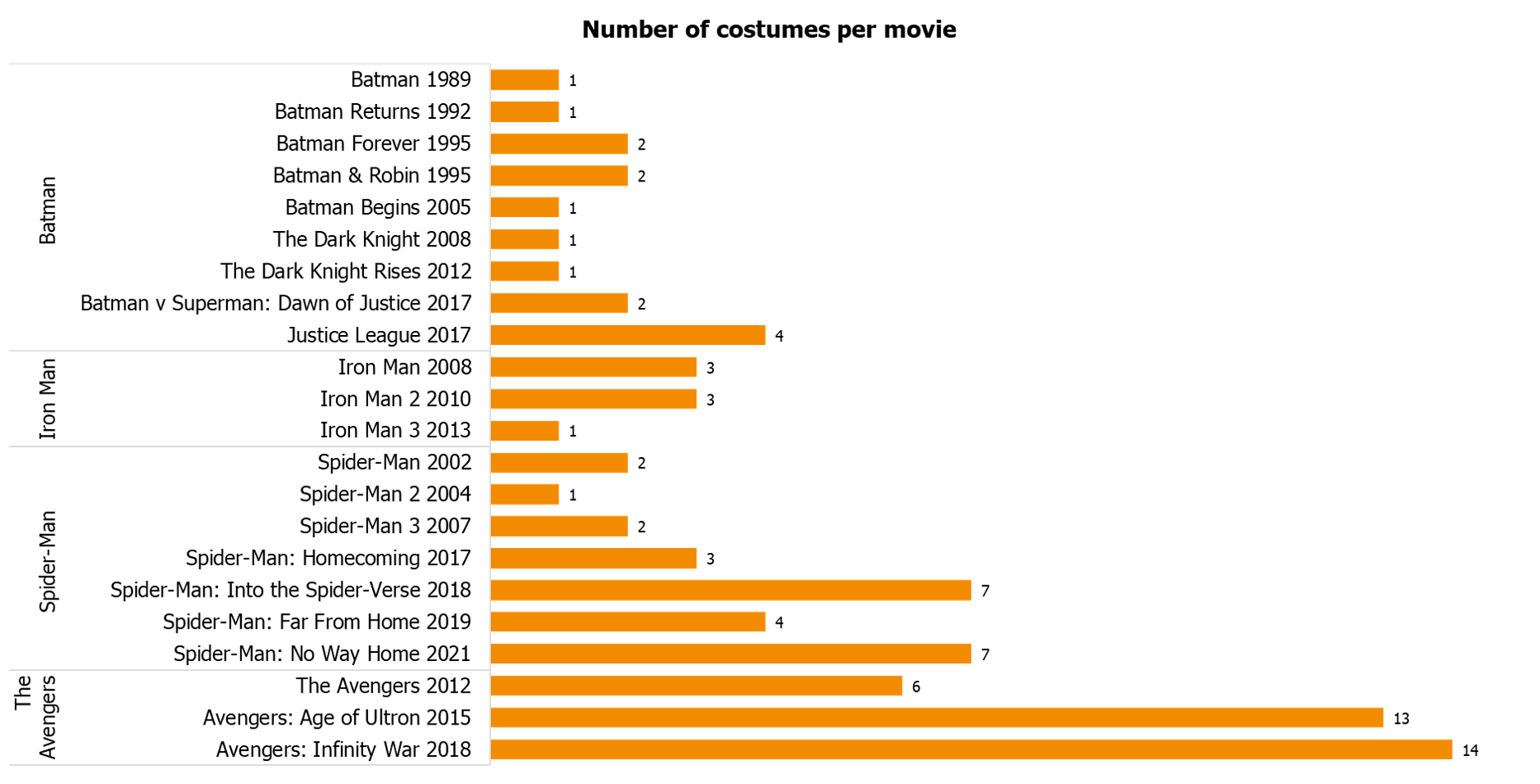

Or can it? Below is a figure showing the number of costumes per movie across the thirty-year period.

As you can see, such films – while keeping the same run time – have massively expanded their merchandising potential, with as many as 14 different costumes in the one film. The question emerges, does this focus on merchandising have impacts on the creative, and the public sentiment therein?

Using a few of these movie franchises as examples, let’s take a look at some times when merchandising has taken top billing, what that has meant for the performance of the brand or franchise, and explore some of the insights other brands can learn from when looking to transform their ideas into merchandising realities.

Iron Man and the MCU

To date, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has made more money than any other film franchise in history. With endless fan-favourite characters to choose from, ‘Spider-Man’, ‘Thor’ and ‘Captain America’, the choice to lead the MCU with the relatively under-appreciated ‘Iron Man’ was a bold choice on Marvel’s behalf. But this decision wasn’t based around which hero looked the best, or who most deserved a silver screen appearance, but rather which toy character kids would most like to play with. Recognising the immense merchandising potential of Marvel’s IP, Chairperson of Marvel, Ike Perlmutter, set about speaking to the main toy-buying audience, kids. Despite a plethora of Marvel heroes to choose from, the results of the focus groups were clear – ‘Iron Man’ was the clear favourite, launching the character to the top spot of the MCU, in addition to kick-starting the MCU itself. The degree to which superhero designs are ‘toy-etic’ would continue to lead creative decisions around stories and characters across the rest of the franchise’s 29 (and counting) films, highlighting the value of those initial focus groups in 2008.

Insight #1: Audience research, including surveys and focus groups, are critical in identifying what the needs of the consumer are, beyond what a brand may believe their audiences seek. What can market research tell you about your brand and products?

Batman

Tim Burton’s 1989 ‘Batman’, a bizarre take on the Dark Knight, was always destined to be a commercial and box office success with the likes of Jack Nicholson and Michael Keaton taking top billing as the Joker and Batman respectively. Yet, while ‘Batmania’ swooped the world in the early 90’s, the inevitable sequels began a downward trajectory in quality and commercial reception, to a large degree because of studio influence demanding the films be more ‘toy-friendly’. Yet, unlike in the case of Iron Man, the studio’s influence was not predicated on relevant data, but simply on what would make the most money. Unfortunately for Warner Brothers, this desire for toy growth constricted the franchise and ultimately killed it with 1997’s ‘Batman & Robin’. In a world laden with reboots and remakes, it’s telling that another Batman film (Batman Begins) wouldn’t grace the silver screen until 11 years later – quite a passage of time for Hollywood…

Insight #2: Merchandising should be complementary to the IP, rather than attempting to supplant it. More generally, this means that brand assets should seek to re-affirm existing brand attributes in terms of what ‘feels natural’, where possible avoiding what just ‘doesn’t feel right’.

Speaking of those ‘truly successful brands’, none other come to mind than Disney. It should then come as no surprise to learn that Disney, the proud owner of Marvel (and thus, the MCU) are fierce protectors of their IP. Yet somehow, they manage to get away with merchandising the stuffing out of their brands, with no evident loss of goodwill. So, what’s their secret?

Disney and Star Wars

The ‘mouse’ is a prolific merchandiser, perhaps because it recognizes that toys and merchandise are just as much for the balance sheet as they are for engagement.

In a documentary about toyification, a fan of Disney’s Star Wars had the following to say about the role of Disney’s merchandising efforts:

“Disney wants fans as engaged in the franchise as possible and is cranking out new ways to interact with the Star Wars world. As a fan, the new and expanded array of opportunities to explore and immerse oneself in the Star Wars universe in completely unprecedented ways, and Disney definitely has the capital necessary to develop these experiences.”

Insight #3: Merchandising offers that which is difficult to attain elsewhere: organic, long-lasting brand engagement. Anything that you can do to breathe life and discussion into your products will help to ensure your brand remains top-of-mind.

Altogether, merchandising leads much of the creative decisions around some of the world’s top film franchises. When done well (see Disney), this can generate immense organic engagement with a brand, not to mention the many billions made in toy revenue. Yet, when done in an inauthentic manner, as in the case of Batman, failure can be attributed to a stubborn focus on the bottom-line, forgoing any market research or data to guide the delicate balance between creative and merchandising.