Does social media owe us social responsibility?

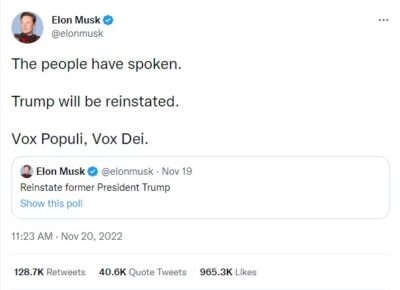

It has been a mere month since Elon Musk took over the reins at Twitter HQ, and in his wake the platform has cast off two-thirds of its workforce, lost half of its top hundred advertisers, introduced and then quickly dumped a misjudged subscription payment scheme, reinstated a number of high-profile censored figures (including one Donald Trump) and lost at least a million followers.

It’s been a swift fall from grace for the app, which was once herald as “the free speech wing of the free speech party,” by the site’s then general manager Tony Wang.

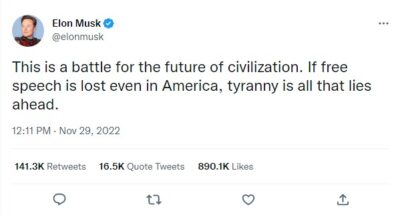

But what Elon’s hostile takeover has achieved is reigniting the public discussion over freedom of speech, censorship and where the onus of social responsibility sits when it comes to social media.

Joel Hill joined Twitter in 2008, but really started using the app in earnest to promote his podcast, The Conditional Release Program. He says that since Elon took ownership of Twitter, many users have become emboldened by his anti-left elite free speech message.

“It appears that the content moderation policies haven’t changed per se, but people who post terrible things are posting with far more confidence than before,” says Hill.

“People feel emboldened to say whatever they like without consequence. Content moderation has always been hit and miss on Twitter – but I am seeing more misses.”

As it stands all social media platforms are self-regulated, and mostly employ a combination of algorithmic and human action to weed out content deemed inappropriate or harmful. In the US, social media platforms are currently protected by section 230 of the Communications Decency Act – which gives them immunity from liability for content posted by third parties on their platforms.

Professor Jeannie Paterson, Law (Consumer Protection and New Technologies), Melbourne Law School, The University of Melbourne says that there is room for improvement when it comes to the self-regulation of social media.

“I think there is potential for better outcomes where social media companies introduce self-governance strategies for ethical, fair and safe conduct,” says Professor Paterson.

“But and this is important, social media is and should be subject to strong law and powerful regulators that, among other things, requires platforms to treat consumers fairly and respect consumer privacy.”

Joel Hill counters that platforms like Twitter should be subject to content moderation from a non-affiliated source.

“At this point, social media companies almost owe a duty of care,” says Hill.

“Banks have licenses. Utilities are regulated. Media is regulated. But social media fits into this bizarre little space where it’s not this, but it’s not that. Regulators find it difficult to balance liability and feasibility – who do you hold responsible, and where is the balance?”

He points to Wikipedia as an example of content moderation done effectively, using the sites own audience.

“A strong midpoint to this would be to moderate with a mixture of automation and crowdsourcing to create an organic regulator which carries the best interests of the community. We are the product; we may as well be the employee as well. Works for Wikipedia. But nobody seems to be having that conversation…” says Hill.

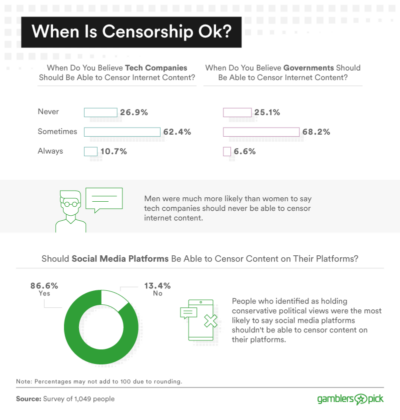

In a study conducted by Gamblers Pick in 2021 on internet censorship around the world, 86.6% of respondents were in favour of social media companies having the power to impose it.

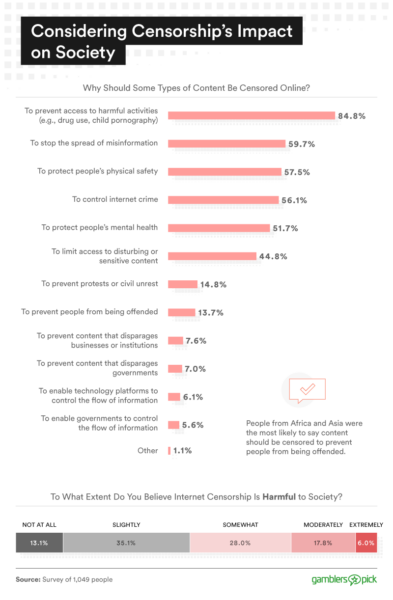

The main reasons flagged by study participants to censor content online was to prevent access to harmful activities (84.8%), to stop the spread of misinformation (59.7%) and to protect people’s physical safety (57.5%).

It can be easy to dismiss social media as a frivolous space full of influencers, out of touch celebrities and commentators too invested in their own opinions, but it was social media that helped give rise to movements like #MeToo and globalise others like #BLM (Black Lives Matter). Citizen reporting has enabled communities to engage with and understand world events outside of the lens of a biased media – with important footage like the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer going viral via Twitter and sparking protests all over the world.

It can also be the stage for dissenters to rally their troops and whip large masses into a violent frenzy. In January 2021, then President Donald Trump had his Twitter account permanently suspended after refusing to condemn his followers who stormed the US Capitol building to try and stop president elect Joe Biden being certified as the next president. Four civilians and a police officer were killed in the riot.

At the time Twitter stated that Trump’s account was suspended due to “the risk of further incitement of violence.”

Whether you view social media as a place to engage with world issues or a vacuous landscape of false idols, it’s clear that these platforms have evolved from their original intention of a connection point for close friends.

“They are no longer hangouts for mates to plan parties (though Facebook has tried and failed to do that with harsh moderation), they are broadcasting platforms and with a platform comes responsibility,” says Hill.

“If a platform is used in a way that is destructive to society, society must react to that. Often with regulations, but also bodies to enforce them.”

Professor Jeannie Paterson says that while free speech is something to be carefully guarded, it shouldn’t be used as a cover for harm.

“Free speech is important but never absolute. You can’t advocate murder, child abuse or genocide. We need to be careful about where the line is drawn,” says Professor Paterson.

“High profile figures should not be immune from those limits.”

Joel Hill doesn’t argue the censorship is occurring on social media apps, but states that it is a vital component of having an online community.

“The issue at hand here is that censorship is considered a bad thing. Free speech absolutism falls apart within minutes,” says Hill.

“Censorship is a way to curb our more terrible instincts. Jacques Rousseau believed that people are inherently good, and society corrupts them. Thomas Hobbes believed that we are all violent, awful creatures that need to be controlled. Hobbes was almost certainly right – and it’s fundamentally human to need to be kept in check – if we are to live in a society that is.”