Does the Australian music industry have a gender problem?

In a blistering keynote delivered at Australian music industry conference Big Sound on Thursday 7 September, Camp Cope frontwoman and solo artist Georgia Maq labelled the Australian music industry a dangerous place for women and gender diverse musicians.

Now in it’s 22nd year, BIGSOUND is an annual four day and night event that touts itself as “the place where tomorrow’s stars are uncovered, and the shape of future business is forged.” The event has been instrumental in unearthing new talent with Flume, Courtney Barnett, The Temper Trap and Gang of Youths (to name a few) all taking to the showcase stage early in their careers.

It also boasts a strong conference program, where industry luminaries and vanguards have taken the stage to discuss the ins and outs of the music industry (past, present and future) with alumni including Nick Cave, Michael Chugg, Peter Garrett, and Billy Bragg.

In Georgia’s fiery address, she covered her experiences in the music industry (which she claimed needed to be fact checked by journalists and cleared by a BigSound Lawyer), outlaying that despite teenage girls being both “tastemakers and the biggest market” for music, women are still grossly mistreated and overlooked by those in power.

“Teenage girls made everyone, from Elvis Presley to Taylor Swift to One Direction, we were the tastemakers and the biggest market, and what did we get in return? Assaulted by men in mosh pits, harassed by men on the street outside, and made to feel as if the space wasn’t ours to be in, like we were just groupies or girlfriends,” said Maq.

“Everyone knew harassment and assault by men happened at gigs and festivals but no one did anything about it, it was treated as though you signed away your right to safety, respect and bodily autonomy as soon as you paid the cover charge into the gig.”

Aside from serious safety issues for both female and non binary punters and performers at shows, Georgia also argued that women and gender diverse musicians have to work twice as hard to get half as far as their cis male counterparts.

“Being a woman in music means you have to work twice as hard as men do, and for women of colour, it’s even more than that. Respect isn’t ever the default for us. We have to claw and fight our way into the rooms men can easily walk into… There’s no winning when you’re a woman in this industry because we are held to a different standard than men,” says Maq.

It’s a sentiment echoed by musican and researcher Hannah Fairlamb, who released a report in 202o with Bianca Fileborn titled Experiences and perceptions of gender in the Australian music industry that explores experiences and perceptions of gender from those working in the Australian music industry.

“My two key findings in that research were that the music industry is a negative place for women, and that it is characterised as a ‘boys’ club’ where men socialise together, share opportunities with each other, and employ each other over and above anyone else,” says Fairlamb.

Fairlamb goes on to add that female musicians are usually seen as accessory to men in performance spaces, and that if they try to bring it up are told that it’s the way it’s always been.

“Many reported having assumptions made about their level of skill based on their gender and that they didn’t know how to play their instrument; being assumed to be the partner of a male musician rather than themselves being a musician; being sexualised and harassed by male audience members, male music industry employees, and other male musicians; and having these negative experiences framed as ‘just the way it is’.”

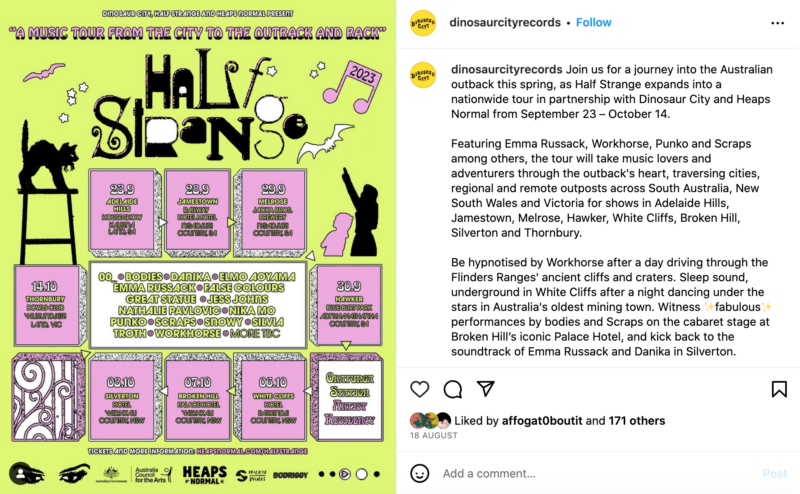

Musician and festival organiser Harriet Fraser-Barbour is no stranger to the challenges of working and performing in a male dominated industry, co-founding a festival Half Strange in 2006 in response to male dominated line ups.

Platforming female and gender-diverse acts, Half Strange is kicking off a tour around rural SA, NSW and Victoria this week, starting in the Adelaide Hills on Saturday, 23 September.

“For me, music has always been a way to unite disparate communities and bring subcultures to the forefront. That’s why this year, I am extra excited to partner with Dinosaur City Records and Heaps Normal to expand upon the festival, taking it to regional and remote centres around the country,” says Fraser-Barbour.

“As a female musician I often feel acutely aware of the ways in which cis-male musicians continue to take precedence and hold centre stage, while female and non-binary musicians have to literally muscle their way into any kind of spotlight.”

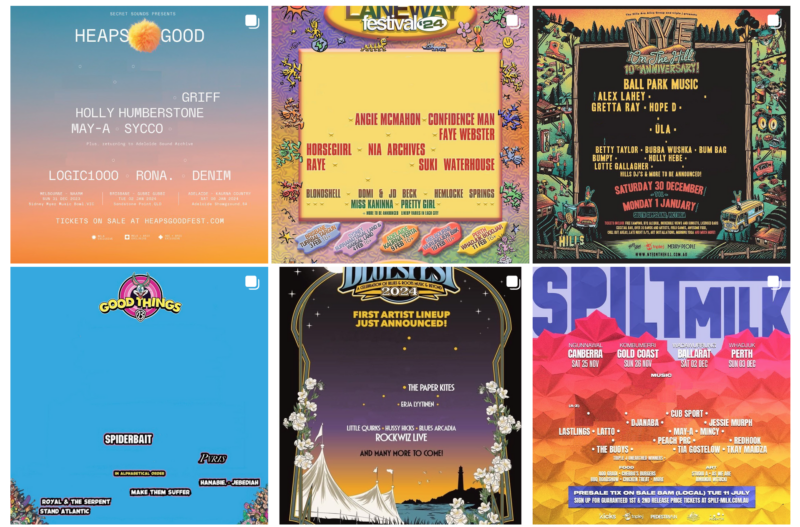

Fairlamb says the festival space in Australia is where the gender disparity can become most apparent – with male dominated line ups the norm.

“The Australian music industry has a real issue with gender representation and safety – you only have to look at things like the Instagram account @lineupswithoutmales (for example) to see how bleak the outlook is for women on a lot of major music festival bills (particularly as headliners),” says Fairlamb.

“This extends to lack of representation of trans people and gender diverse people in the music industry. There’s also some really specific issues around sexism intersecting with other factors like ageism for example.”

In Georgia’s speech she outlines some of her suggestions for change, starting with “more women in leadership roles in the industry… more women and non-binary people being supported and encouraged to enter roles like production and engineering.”

She also added that the industry needs to listen to women when they expose abusive men and hold those men accountable, for more opportunities for women on the main stages at festivals, for streaming platforms to fairly pay artists for their music and for Australian radio stations to support and play home grown talent.

On what it would take for the industry to proactively work on a safer, more inclusive environment, Fairlamb argues that it’s up to everyone who hold positions of power to use their privilege to make the industry more inclusive for all.

“I think it will take those in positions of power and privilege – mostly cis-het white men, but other privileged people as well (myself as a cis-het white woman!) – to deliberately reach out with empathy and ask, what is my responsibility here? What opportunities do I have to include people? How can I make this space safer? How can I provide opportunities for people that don’t often have a platform to tell their story in their own way?”

“That’s my solution. Empathy on purpose.”