Is Instagram’s draconian code of conduct impacting the creativity of artists?

Instagram has allowed a wide rage of people to discover art, since it was launched in 2010. It has also allowed artists to ‘exhibit’ their work to a wider audience without borders – and receive feedback in real time. But as with all social media, the relationship between art and the fabricated world of the web is complicated – with Instagram’s harsh and broad-stroked guidelines and codes impacting what artists can and cannot share.

In an article on CBS titled ‘Is Instagram Ruining Art?’, New York based painter Riah Miah argues that while some galleries are adapting their exhibitions for social media, seeing a work in the flesh is still the ultimate way to engage with art.

“It’s the subtlety of seeing something in person that makes a work art, whereas seeing something on social media is just an invitation to get the conversation started.”

But how is Instagram restricting that conversation?

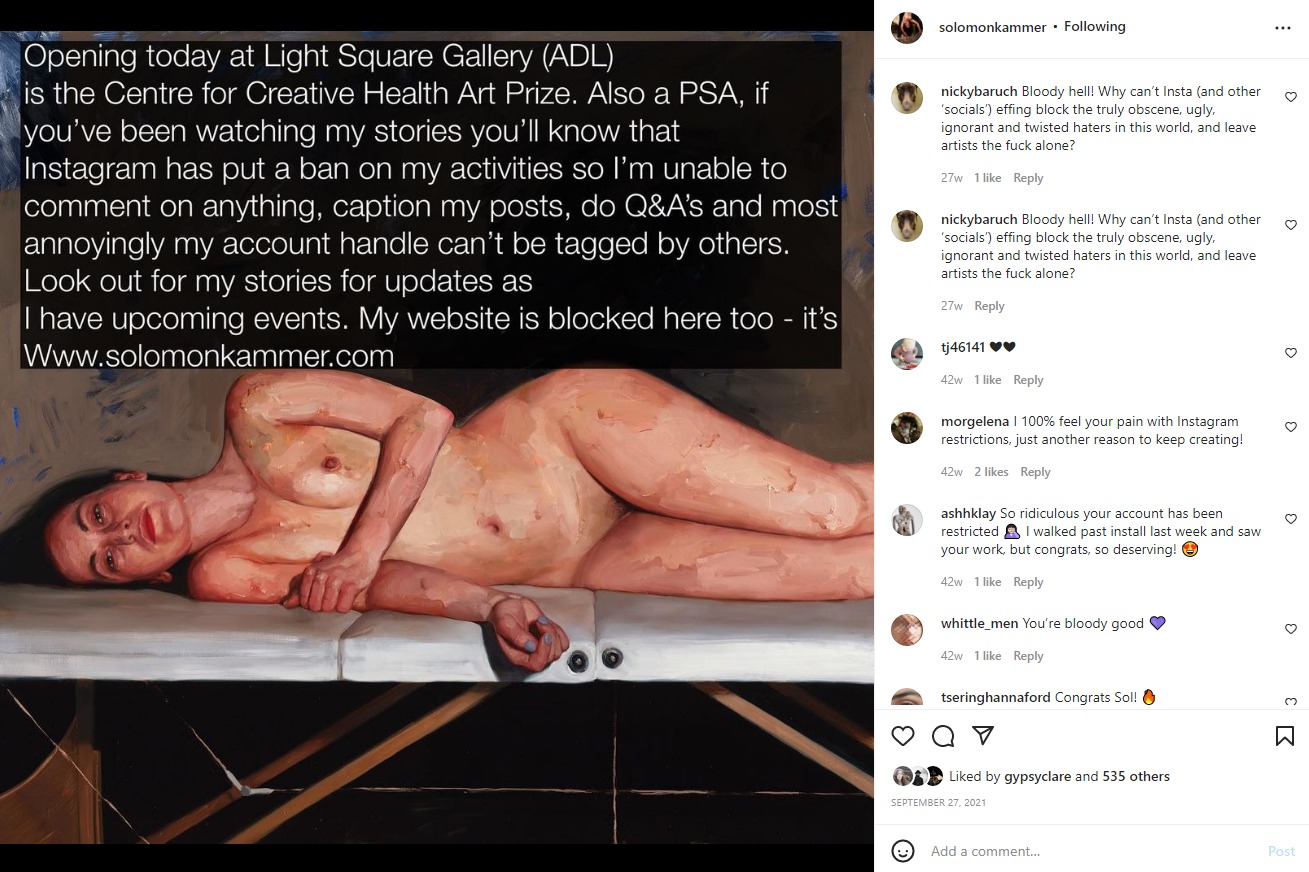

For many artists, Instagram has become a calling card that can lead to sales, gallery representation and exhibitions. One such artist, painter Solomon Kammer, says that the impact of Instagram on their creative business is multifaceted.

“It’s really important to me. I use it as my portfolio. I think a lot of people in the industry, peers, curators, and other people I need to connect with as an artist, use it as well as a connection point. I also used to get clients from Instagram who would buy my art. It’s the main tool that I use to connect with the universe and share my work and promote it,” says Kammer.

A 2022 Archibald Prize and 2021 Ramsay Art Prize finalist, Solomon’s paintings are raw portraits of medical intervention into female and non-binary bodies, sparked by their own journey for an endometriosis diagnosis. Their art acts as a form of protest and advocacy to challenge culturally embedded notions of ‘womanhood’ – but due to Instagram’s restrictive outlook on nudity, their work usually falls foul of the image sharing sites guidelines and code of conduct.

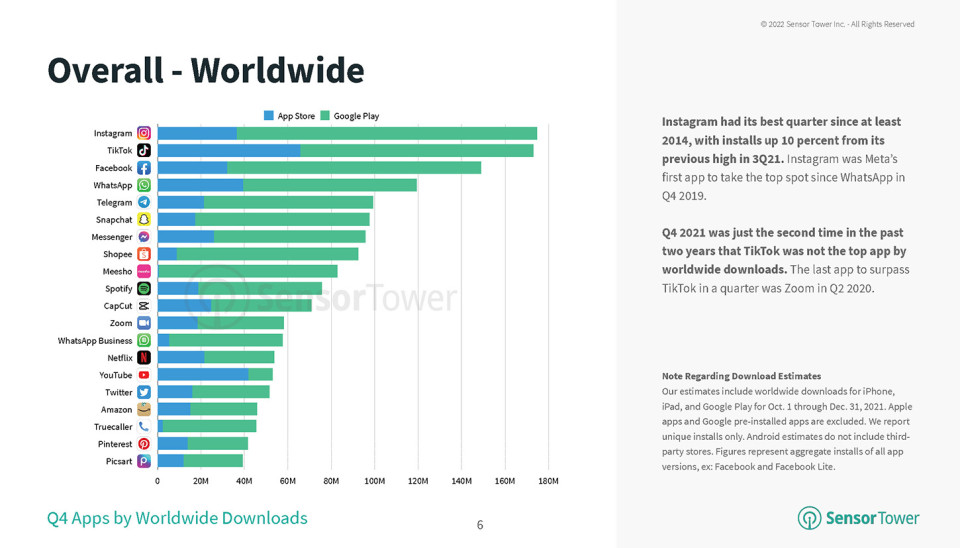

The impact of Instagram marketing for artists can’t be downplayed, with the app leaping four places from number five to the most downloaded app in 2021’s 4th quarter – with over 1 billion users logging into the app on any given day and spending an average of 53 minutes per day perusing content.

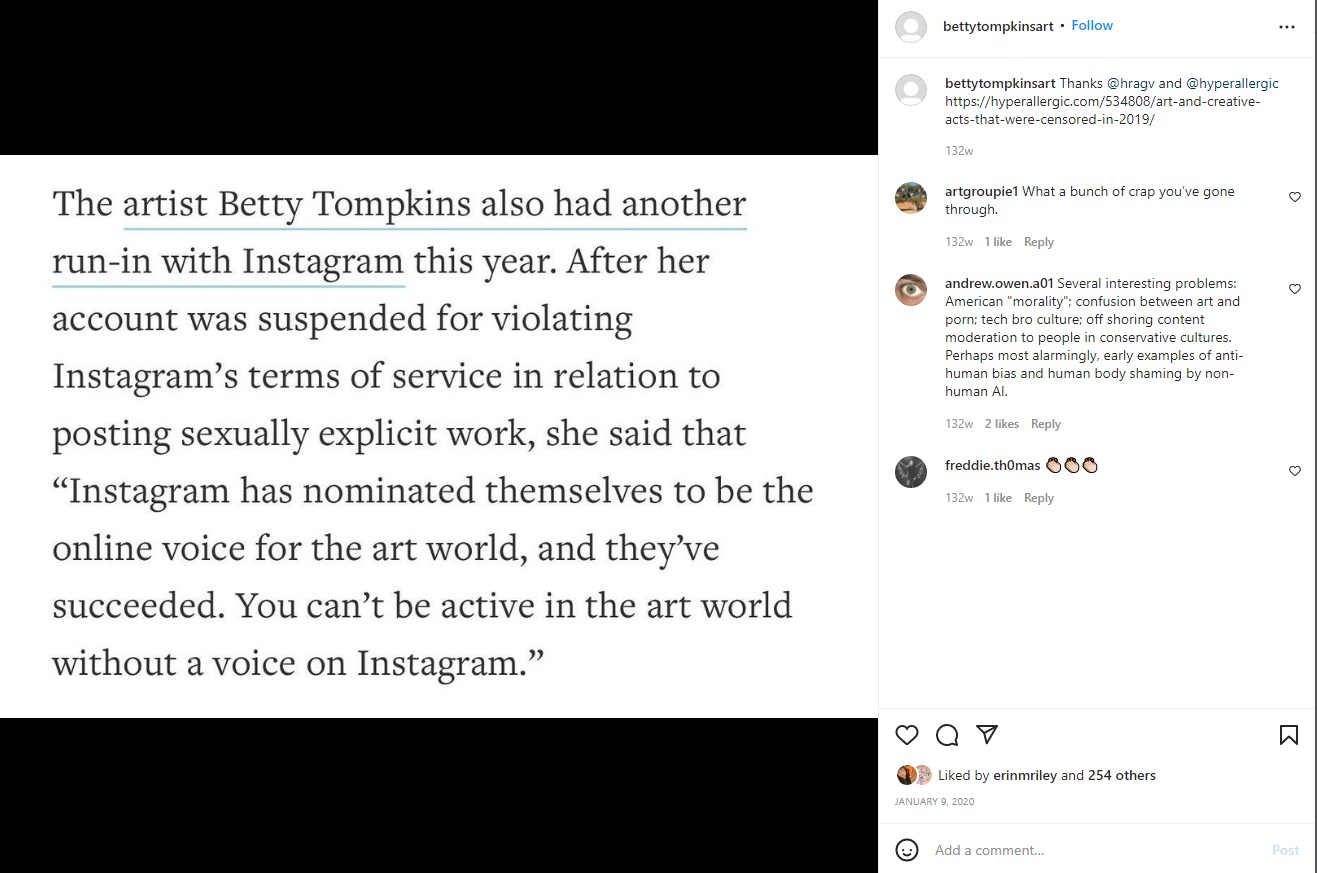

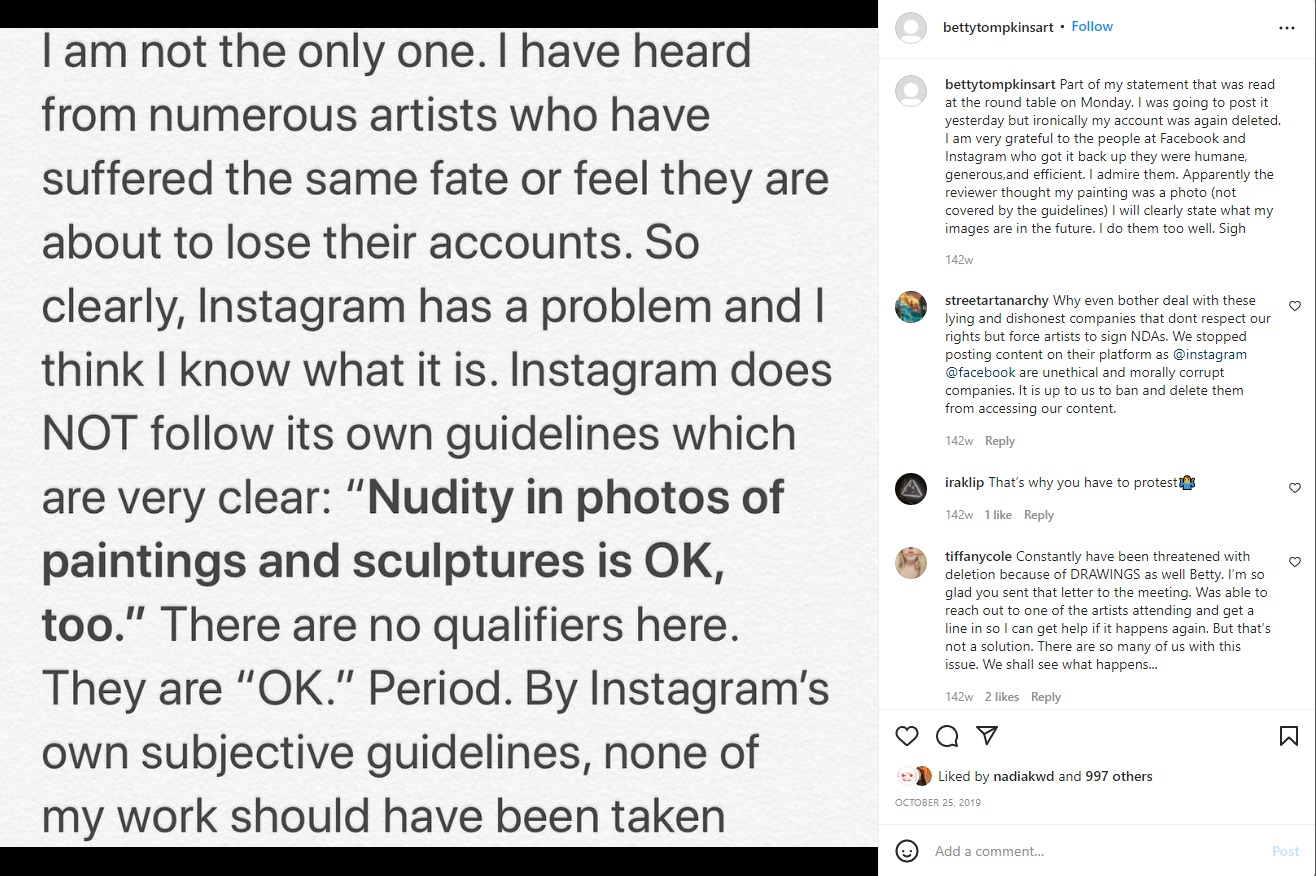

In an article on The Art Newspaper, US artist Betty Tompkins, who was blocked from Instagram for several days in April 2019 after posting an image of her photorealist Fuck Painting #1 (1969), says that Instagram have a content stronghold, that leaves artists with little option for redress.

“It’s so scary because we all use social media, and Instagram in particular, to advance our careers. The first thing that really struck me when the account was down was, ‘Oh, my God, how am I going to advertise this show?’ They are censoring me personally, as an artist,” says Tompkins.

Solomon says that Instagram’s push towards paid content is hurting small businesses, while also putting those artists deemed too controversial for advertising at a huge disadvantage.

“My engagement is far, far less because I can’t spend the money (to boost posts) because my content prohibits me from spending money on advertising. Therefore, it limits my reach, which in turn limits my influence. And that’s difficult because Instagram actually does have a place in legitimizing people’s careers,” says Kammer.

“It is really impacting the perception of success. I’m having trouble getting new engagement, and new followers. I’m just kind of sitting stagnant. I’m not really growing anymore.”

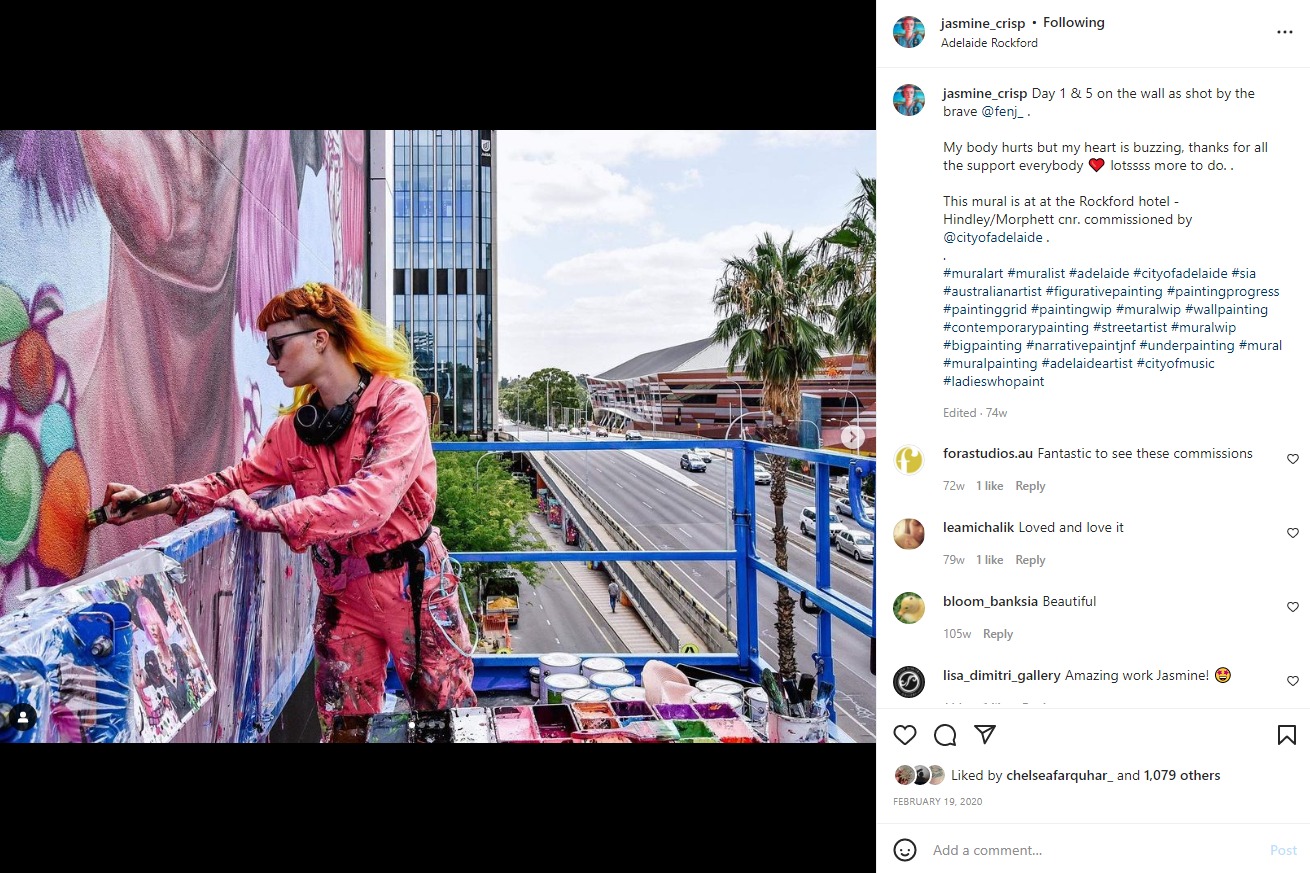

For portraiture artist and muralist Jasmine Crisp, the restrictions around what can and cannot be posted to Instagram mirrors the hoops mural artists have to jump through to have their designs considered for public spaces.

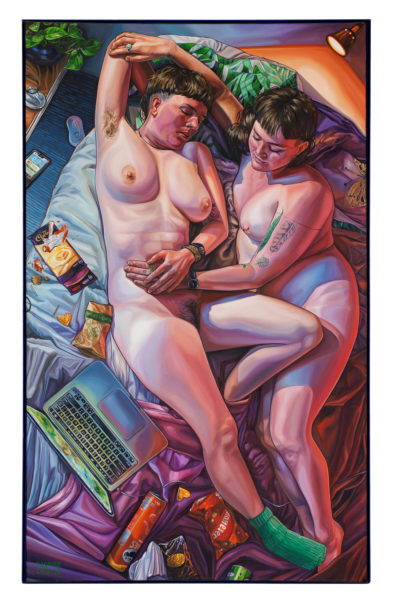

Jasmine’s work regularly shines a light on the intimacy of private rituals and moments undertaken by couples and individuals in the safety of their own homes.

“I feel like it has a really similar feeling to when I make public art, versus when I make work in the studio – where Instagram is a public platform. You do have this inherent guard up of censorship or appropriate behaviour. Because people are seeing it and you don’t want to cause too much of a stir, so you’re probably less likely to share things that are very bold or very brave or very controversial,” says Crisp.

“It is problematic when it limits what you can create, particularly when we’re talking about nudity in art.”

Back in 2019, Betty Tompkins sent along a letter to be read aloud at a demonstration outside Facebook’s Manhattan Headquarters. Facebook had invited a select group of artists that had all at one time been censored by the platform (including Marilyn Minter and Micol Henron) to a closed-door meeting about their concerns.

In her letter Betty wrote, “As it is currently, the system is arbitrary and discouraging for any artist whose work is challenging or thought provoking.”

Despite a vague promise of a reconsideration of nudity guidelines, and as Instagram and Facebook herald in their Meta era, things are just as dire as they were three years ago for artists. Now instead of receiving a warning for nudity violations, users are being cautioned for ‘Adult Sexual Solicitation’ when they share art with nudity. The author of this article recently received such notice when I shared an Instagram post of the painting by Jasmine Crisp below, titled, ‘They watched David Attenborough and waited for the world to end (a portrait of Georgy & Heather)’.

In a leaked memo by Meta’s new CTO Andrew Bosworth, he revealed plans to institute “almost Disney levels of safety” – with the battle for censorship in art looking to take on new heights as the company expands into unknown territories.

Despite the mounting pressure, both Jasmine and Solomon remain resolute that their content will not be impacted by censorship rulings by any institutions.

“Although I don’t think rules online or just in the public sphere will determine what work I continue to make, it will perhaps determine what decisions I make in terms of promotional imagery,” says Crisp.

“The content of my work is so integral to the message I’m trying to put across with the work. So, I’ve never thought about compromising in that way. I don’t think it’s up to me to bend to their rules, I think it needs to be addressed and dealt with by Instagram,” says Kammer.

“I’m just going to keep doing what I’m doing and wait till they figure out a way to be more inclusive.”