Does Australia’s sense of fairness and the little Aussie battler actually exist?

Australia loves the narrative of the Aussie battler, the underdog triumphing, against the odds, the larrikin breaking the rules. Yet, we don’t like people too big for their boots, and are generally blind to those without the privilege necessary to succeed. Is Australia’s sense of fairness and supporting the battler actually a load of bull dust?

Larrikin is an Australian term referring to a boisterous, often badly behaved man with apparent disregard for convention.

A couple weeks ago my daughter and I simultaneously hit 50 parkruns. When we first started, I won every week, now she beats me. I call it empowering her, she calls me being too slow (or OK for my age).

Last Saturday, heading to the week’s 5km group run along the Torrens River in Adelaide, news came on the radio that spin-bowling cricket legend Shane Warne had died aged 52.

Too young to die, it turns out only two weeks younger than me. Warne gone from a heart attack in Thailand. The quintessential Australian sporting legend larrikin had died. RIP Shane Warne, so very sad.

But. today’s piece is not about Warne, nor me. It did get me thinking about how we create greatness in Australia, and is it really fair?

Australia loves a larrikin, and Shane Warne’s sporting triumphs, and larger than life cricket to Hollywood lifestyle, rollercoaster of emotions and relationships and authenticity made an endearing story.

In a 2018 interview with Leigh Sales, Warne talks of media giant Kerry Packer telling him to “sell that silver Ferrari, people are gonna think you’re a big head,” and he shares the joys and challenges of living up to the idealised Aussie larrikin image of supporters. An insightful interview.

Watch Leigh Sales interview via below link …

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zIPOpbCL4mo

Going back Warne won a sports scholarship for years 10 to 12 at top-tier Melbourne private school Mentone Grammar, which likely guided him down a sporting career path. At age 18 Warne was rejected from the St Kilda Football Club, which spun his full passion and obsession towards cricket, playing for the University of Melbourne and eventually at the highest level. A talented sportsman recognised from a young age.

In Australia’s sense of fairness we love the idea of the larrikin battler. In this we can forget how important the opportunities (and set backs) are in guiding the way forward, and that not all Australians have such privilege, networks and support from an early stage.

Cultural legends such as Warne come from opportunities and recognition that drive a passion. The little Aussie battler doing good is likely a rare exception rather than the norm.

I wrote an article last year about privilege, inspired by a large education study we were conducting in which myself and our team spoke with people via focus groups, in-depth interviews and surveys in a lower socio-economic status area with stigma and ofter low self esteem …

“A participant in her 40’s talked of ‘privilege,’ and how life is often not fair. Her disadvantage early in life had made paths such as university an unimaginable luxury. She noted that even hard work won’t overcome lack of privilege. This now self-accomplished lady, told of how she became homeless straight out of school, moved around a lot, and worked hard to eventually achieve a good city job.

She prioritised a good education for her children. A home mortgage in an affordable area, and she worked hard to provide a safe environment for her children, and reminds them often of their ‘privilege,’ and the importance that they respect others without.”

In another discussion in the same project, a seemingly typical female school student (year 10), talked calmly of needing to “grow up quickly” and move out of home at a young age, to far away from her family, to fend for herself. She was strong, and had a supportive school, but life wasn’t totally fair as other young Australians. Strong teaching roll models were critical for her, as her parents and family were out of the picture.

Success in Australia skews towards privilege, old networks, schools and exclusive clubs. Rather than moving away to study, there can be a pull to stay home for work or university in Australia. Often piped from kindy to school, university and career, to well networked board roles for the exclusive few. An introspective perspective. This can be multi-generational tried and tested paths, generational wealth and privilege. While Australia provides a foundation to build opportunity over generations, it is often far less fair than we’d like to acknowledge.

Just over 40% of Australians move every five years, more than twice the worldwide average, yet 85% of Australians who move each year stay within the same state. (A nice summary here >)

Last Friday morning I interviewed a 60 year old Aboriginal lady who told her story as a school aged girl having a black box delivered to her front door unexpected. It contained a clarinet, and through a series of fortunate opportunities and programs, she had a successful music career. Music was not just a career for her, but her children and family.

Many of those in her music community as a young person were from the stolen generation, and the connection provided valuable sanctuary away from lives of instability and chaos. She lamented that much of the education and other programs she was privileged to have access to had been unfunded in recent years, so emerging generations of young first nations are not guided away from a life of chaos and instability.

I’ve been fortunate over the years to have been involved in many studies in disadvantaged communities. Beautiful young people, with dreams and hopes, yet often complex home lives and a lack of mentors and support structures to guide them towards a better reality.

Underage destructive behaviours from smoking to drugs, alcohol and violence were the default, and a reality they hoped to overcome, but it was hard to see the path out. Self-esteem, inter-generational unemployment and under education, obligations at home to care for and support parents / family and even geographic isolation and travel time were all seemingly insurmountable.

Progress going backward, young people at real risk, ignored.

It has been interesting in our research around cultural diversity at how the second generation of migrants to Australia are often grateful for the sacrifices of their parents in coming to a new country, facing questionable fairness at times, and from hard work and determination they create opportunities for the next generation. Yet, even so, cultural divides and frictions are still common.

Subtle racism, hidden bias and the bamboo ceiling still exist in Australia.

An interesting excerpt from a May 2020 AFR article …

“The proportion of directors from non-Anglo-Celtic cultural backgrounds fell to 5 per cent from 5.4 per cent between 2016 and 2020, the study by the Governance Institute of Australia and Watermark Search International, an executive recruitment firm, found. The proportion of board directors from anywhere outside Australia declined to 29.3 per cent from 30.4 per cent over the same period.

The lack of cultural diversity at the board level reflects a similar pattern at executive levels, with a 2018 report from the Australian Human Rights Commission, University of Sydney, Asia Society Australia and Committee for Sydney noting that only 5.1 per cent of chief executives and senior executives in Australia had a non-European or Indigenous background.” More >

In a recent research discussion I had with second generation migrant young adults, they discussed how they still do not feel welcome in their own country, even often with impressive academic achievement funded by their parents who have worked hard for the next generation.There are so many aspects of Australia in which opportunities are imbalanced, and while there are many efforts to correct this, for many inequality is the reality. The role programs and support reaching those who might be missed – sport, the arts, professions, entrepreneurship and beyond – is critical.

Work of groups such as the Polly Farmer Foundation supporting young Aboriginal people to success from school and beyond. Or Helpmann Academy in empowering emerging creatives. There are many programs supporting young people and to provide them with recognition and opportunity. There are so many wonderful programs for young people.

Yet, it is worth ever keeping a reality check on the sense of fairness, including for those without the luck and privilege of the select few.

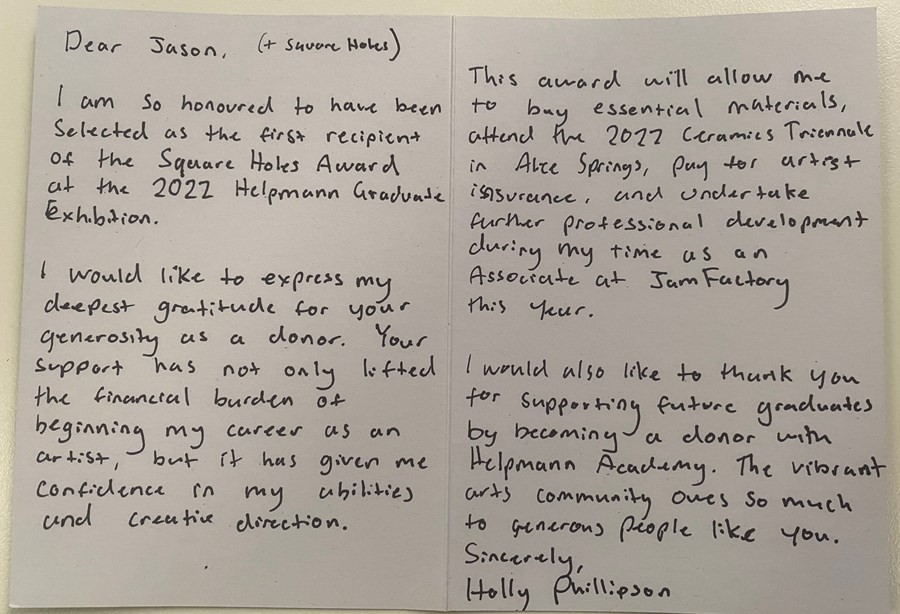

Square Holes recently awarded the inaugural Square Holes Helpmann Academy emerging artists award! Valued at $5,000 (cash) selected by judges. We were pleased Holly Phillipson (insta > instagram.com/hollyphilli). I love Holly’s unexpected thank you card as to how valuable such support is, to keep her passion alive.

(View Holly’s awesome art via here >)

The award was inspired by contra / sponsored research we have conducted for Helpmann for the past five or so years. It has been fascinating to interview such amazing young artists from music to visual and otherwise, who are able to use a relatively small amount of funds to recognise their ability, open up opportunities and to keep going, when the signs financial and otherwise are saying to take an easier route.

Our research for start-up initiatives such as SouthStart illustrate how critical programs are to find, empower and support the next generation of entrepreneurs to succeed. I can recall interviewing Flavia Tata Nardini the CEO of growth satellite innovator Fleet Space around how important it is to provide a lighthouse, internships and opportunities for those not as privileged, or outside the more exclusive network, or too afraid to enter.

There are ever new opportunities for young people, yet allowing access and pathways is important to ensure suitable candidates are found.

Another quintessential Aussie larrikin battler is music legend Jimmy Barnes. One of Australia’s most legendary musicians, the Scottish-born, volatile lower socio-economic upbringing, Elizabeth South Australia raised voice behind anthems Khe Sanh and Working Class Man, was inspired by older brother Swanee (appointed an Order of Australia Medal in 2017 for contributions to music). A love of music that pushed Barnes through many challenging years to ultimately triumph. As Jimmy Barnes was about to give up on Cold Chisel at age 21, the final farewell concert triggered a record deal with WEA and icon status.

Jimmy Barnes (now with an Order of Australia) is from true working class pedigree. Starting his working life as an apprentice at a foundry for the South Australian Railways. What’s interesting is Australia has a well paid working class comparing globally, partly from reforms introduced by our last working class Prime Minister Paul Keating, a self-educated man who left school at 15. (More via ‘Beyond bogan: what happened to Australia’s working class?’ Monash University June 2018)

There is a role for one generation to provide opportunities for the next. My parents moving our family away from Swan Hill in country Victoria (population around 10,000) when I was four for work, around 10 homes before high school, created opportunities and opened more accessible university and career pathways, and inspiration to understand people.

From this we have been able to provide opportunities for our own children (and a level of privilege), situations to expose them to pathways and inspiration. For Miss 18, an opportunity to attend NASA Space Camp in 2019, local school space opportunities and good role models, likely guided her towards an impressive year 12 result, entry into a very male dominated university study in Mechanic Engineering, and proactively seeking and accessing internships at local space enterprises.

My taxi home last Saturday night was driven by a bright young Mechanical Engineering graduate from a multicultural background, struggling to find work, to navigate the local employment market, facing biases and perhaps not given the same opportunities as others.

In many ways the little Aussie battler is a myth, as it seems is Australia’s true sense of fairness. Australia has so many role models for success. Yet, fundamental in this is support at an early stage to recognise their potential and ignite their passion. Likely the key to a successful life is seeding potential opportunities from a young age.

This should not be for the privileged few.

Think about the successes that may be missed or opportunities ignored for not empowering the next Warne, Barnes, Nardini, Phillipson or otherwise. The role of support from school to early adulthood is critical.

Let’s seek ways to create greater fairness in opportunities for young people, and the better Australia this will create.