What does the Queen’s death say about Britain?

When I was a child, my Grandmother reminded me of the Queen.

We only visited Swan Hill in Victoria about once a year growing up, so there was some level of disconnect, and with a large swag of cousins who lived nearby with a closer relationship, the best way to describe our relationship was aloof. I can recall one time, at a family dinner, needing to walk the long way to the head of the table and ‘kiss’ my grandmother in a sign of deference. As the wife of the local Mayor for a period, there was a feeling of royal connection and even respect for our family matriarch, yet when my grandmother died, as a child my feeling was more so one of an inevitability, than a particular overwhelming sadness.

For many of the 250,000+ enduring the up-to 30-hour wait to view the Queen’s coffin, they seemed to show more personal sadness at the loss of a (non-) family member than what I felt for my own grandmother. While I can to some extent understand the emotional show of respect for the Queen’s 70-year reign, it did seem to be an indication of how much Australians differ from the people of Britain.

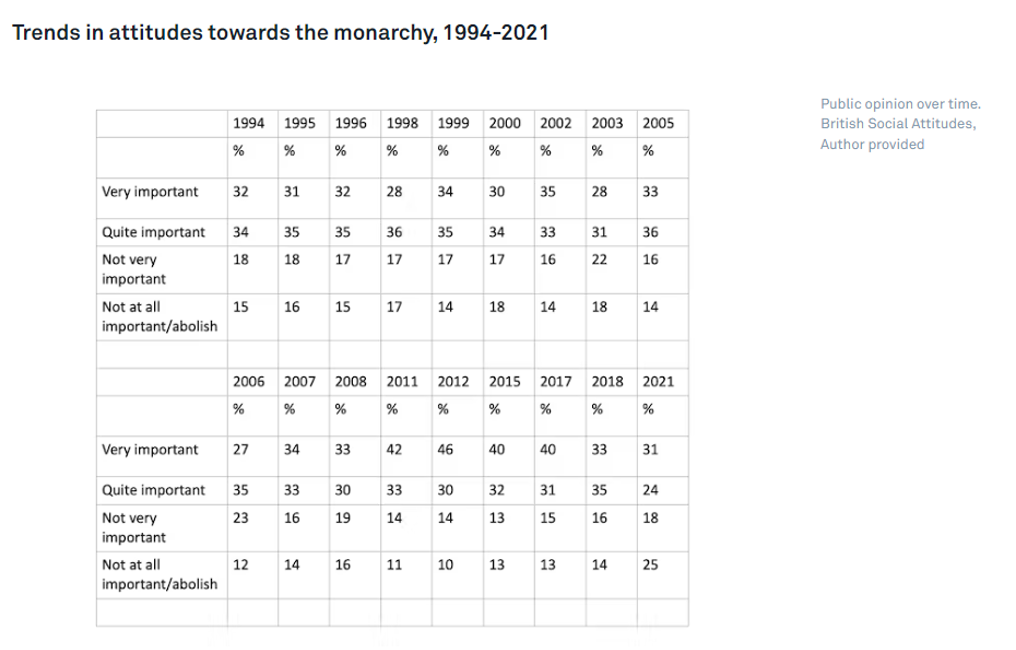

Britain’s class system was televised to the world. While Australia’s tall poppy syndrome takes the air out of anyone wishing to be too big for their boots, Britain (official collective name of England, Scotland and Wales and their associated islands) seems to embrace the monarchy and the entrenched class system it represents with a sense of immense pride. Consistently over recent decades, two-thirds of the population view the monarchy as important, 66% in 1994 and 55% in 2021, according to the British Social Attitudes survey. The 2021 result was well below the 70%+ between 2011-2017, even so the majority support.

As might be expected, monarchy support is skewed older.

In a survey of 1,710 adults in Britain (13-14th of September 2022) in the week following the Queen’s death, 86% of those aged 65+ believed Britain should continue to have a monarchy in the future, with this number declining with age down to 58% of 25-49 year olds and 47% of 18/24 year olds. And, when asked how strongly they hold this view, 81% noted this as a strongly held view.

Other key statistics include …

- One in five agreeing there should be a referendum on whether or not Britain should continue to have a monarchy (relatively consistent across age and gender, lower amongst conservative voters)

- Around half (52%) believe Britain should have a monarch in 100 years, 18% don’t know and the balance (30%) ‘no’

- Older Britains are more likely to be proud of the monarch, younger more split between proud and embarrassed

- Support for King Charles is strong, again particularly amongst older and conservative voters

A large proportion of Britain’s population support the monarchy, even younger people. It would seem from this and the media coverage around the Queen’s death, that there is a difference in values compared with other, predominately English-speaking countries, Australia and the US, around willingness to accept a class system.

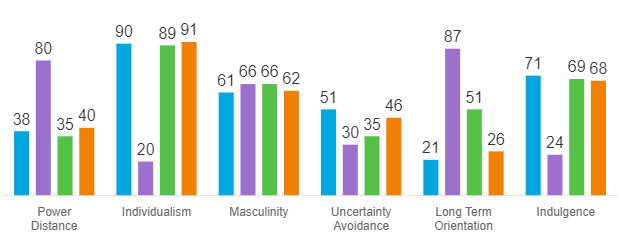

However, according to the Hofsted Culture Compass, there is a great deal of general consistency between Australia, the US and UK, with the UK actually slightly lower in ‘Power Distance’ i.e. a society willing to accept inequalities amongst people. While a country such as China has a comparatively high ‘Power Distance’ rating and low ‘Individualism,’ there is a general consistency for predominantly English-speaking countries.

COMPARISON OF AUSTRALIA (Blue), CHINA (Purple), UK (Green) and US (Orange) ACCORDING TO THE HOFSTED CULTURE COMPASS (More >)

What is interesting about this for the UK, is that for higher class Britain ‘Power Distance’ is lower than amongst the working classes. What is revealed in the data is one of the critical frictions in the British population. Inherent tensions between the importance of birth rank on the one hand and a deep-seated belief that where you are born should not limit how far you can travel in life. A sense of fair play drives a belief that people should be treated in some way as equals.

Research has illustrated that Britain’s class system is a key determinant of future prosperity. This includes mobility and ability to move home to higher status areas, and there was a strong link between geography and future prosperity.

Of those with “higher managerial” and “professional” parents, around 60% made at least one long-distance move, while only 30% of those whose parents’ occupations were classed as “semi-routine” or “routine” had moved areas.

“Among higher managers and professionals, those with advantaged backgrounds lived in more affluent areas as children than those from disadvantaged backgrounds,” said McArthur and Hecht, who was formerly based at the Politics of Inequality research center at the University of Konstanz in Germany.

“This area gap persists during adulthood: when the upwardly mobile move, they are unable to close the gap to their peers with privileged backgrounds in terms of the affluence of the areas they live in – they face a moving target.

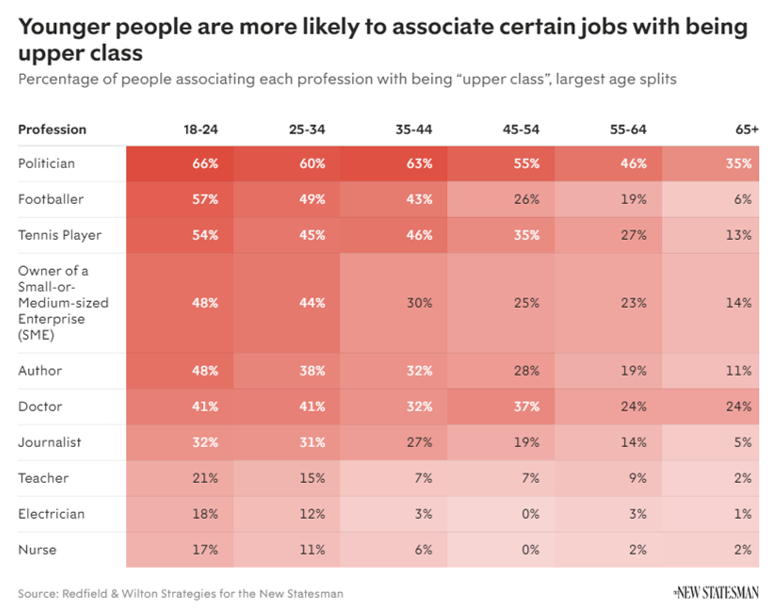

There is also evidence from Britain that the definition of the class system is changing, particularly amongst Gen Z and millennials, to be less about the rights from birth to other determinants such as salary, assets and holiday locations. Interestingly, younger British are more likely to associate a wider range of occupations with being upper class.

Clearly the period of mourning of the Queen’s death was largely a sign of respect for a long-standing monarch who was viewed by many in Britain and beyond as making a significant contribution over time. It is interesting that there is a wide range of perspectives as to what the Queen represented. A monarchy as a signifier of a class system more favourable based on birth, rather than other factors. Or for many, such as First Nation Australians, as a signifier of the evil side of Colonisation, and the continuing injustices since. The Queen perhaps mourned as one’s grandmother, but in reality, far from the intimate relationship some perceived.

Interesting links …

Mourning a Monarch: Why People Cry For Virtual Strangers