Australian news media has a diversity problem

A damming ‘report card’ on Indigenous and cultural diversity in Australian television news media outlines that Australia still has a long way to go when it comes to adequately representing our multicultural population.

Released in late November 2022, The Who Gets To Tell Australian Stories? 2.0 report was led by academics from the University of Sydney, in partnership with Media Diversity Australia (MDA) and the Jumbunna Institute at the University of Technology Sydney and is a follow up to the landmark report of the same name released in 2020.

The multi-method research study included a broad investigation of over 25,000 news items on 103 news, current affairs, and breakfast TV shows over a two-week period, along with audience and staff surveys to gauge attitudes on indigeneity and cultural diversity in Australian news, and a comparison with international media.

The report is the first forensic examination of how our media treats cultural diversity at a workplace level – examining the experience, inclusion, and representation of cultural diversity.

Dr Lee Martin, senior lecturer at the University of Sydney Business School and co-author of the report, says the first study (2020) and this subsequent follow up were prompted by Media Diversity Australia (MDA) as a way to track and report on the evolving state of media diversity in Australia.

“There wasn’t any publicly available, industry-wide evidence-based information for the level of cultural diversity in Australian news and current affairs programs on TV before this study. So, the idea was to measure the scale of the challenge that lay ahead and also to get some insight into working journalists’ attitudes, that would form a baseline to measure against,” says Dr Martin.

“Presenting this evidence and data to the public makes it hard for industry to look away. This latest report provides the critical information that is needed to make sure that attention stays on this problem.”

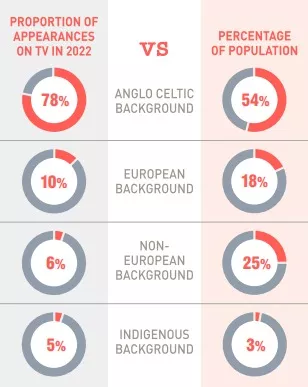

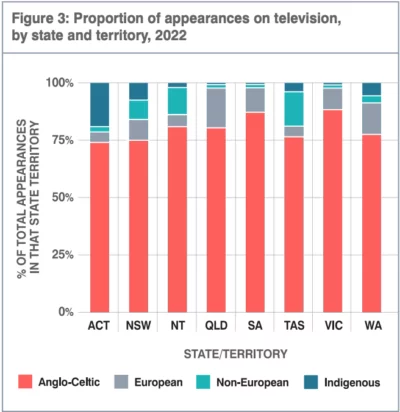

The 2022 report reveals that not a lot of headway has been made in terms of diversity efforts from many of the major media institutions, with more than three-quarters of presenters and reporters across all networks (in terms of numbers) coming from an Anglo Celtic background (a slight increase from 75.6% in 2019 to 76.0% in 2022). According to the research, in proportionate terms, the Anglo-Celtic background is over-represented in presenters and reporters, given that an estimated 54% of Australians have an Anglo Celtic background. Presenters and reporters in the other three categories – European (13.1%), non-European (8.1%) and Indigenous (2.8%) – remain under-represented in 2022, compared to their proportions in the general population of 18%, 25%, and 3% respectively.

Ash London, a Lebanese Australian radio, and television personality says that representation matters, as so many Australians use commercial news and current affairs programs to build their opinions around major events and communities.

“I think we forget that for a majority of Australians, this is where they’re getting their information from. They’re not reading the studies, they’re not reading articles that aren’t sensationalized, they’re turning on the television, they’re learning from commercial free to air, and that’s the lens by which they’re forming their own opinions about the world,” says London.

“So, if they’re not hearing opinions and proper discussions from people who have got some skin in the game, have some real lived experience, then we’re not going to have diverse opinions. We’re not going to have proper discussions. And those loud opinions that we’re hearing are from people that shouldn’t really be commenting, but instead should be listening and we don’t see a lot of listening.”

Dr Martin adds that a wider breadth of diverse voices on our screens leads to a more inclusive Australia.

“It’s of great benefit to ensure that diverse voices are represented in our media, because you’re going to have better quality journalism, in terms of more nuanced and balanced reporting,” says Dr Martin.

“That then has flow on benefits to a more cohesive society because once you have more balanced reporting, and greater variety in the stories being told, you then get a richer understanding of the people and events that are happening around you.”

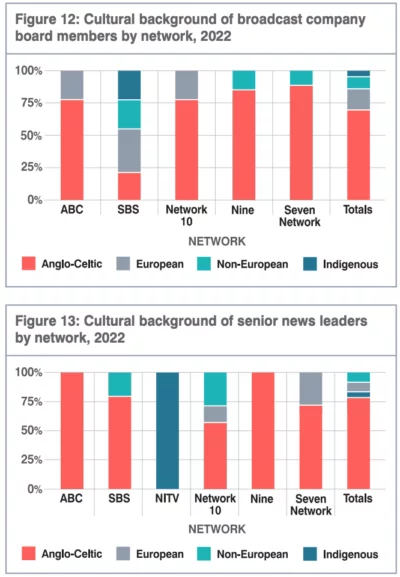

The study also scrutinises the board and newsrooms behind-the-scenes, mapping the representation of the leaders and editorial staff responsible for what stories make it to front of camera.

In an op ed for The Sydney Morning Herald, Antoinette Lattouf, broadcaster, author, and co-founder of Media Diversity Australia writes, “Of course, it’s not just who is on our screens that matters. When we analysed network board directors and television news leaders, the root of the problem becomes clearer. The ABC board includes not a single First Nations or non-European leader. The boards of Nine Entertainment and SevenWest Media each have just one face of non-European background. While SBS has representation on its board, there are big diversity gaps in its TV news leadership. Ditto for Nine and Seven, where gender representation is also a problem. Those calling the shots and framing the narrative don’t look or sound like the Aussie audience.”

Dr Martin says that it was important for the researchers to really delve into representation behind the screen, as well as in front, to get into the systemic issue of lack of diversity.

“They’re the ones that hold the power and influence to actually make changes to the organization that can improve diversity, equity, and inclusion in the longer run. Not just in front of the camera, but also behind the camera because the lack of diversity on our screens is a systemic problem in media organizations,” says Dr Martin.

“Therefore, just tackling one aspect of the problem, which is the on-air diversity that we see on our screens, that’s not going to necessarily bring about sustainable change for the whole organization.”

The report also outlines a number of actionable adjustments and structural changes for institutions to undertake, including internal tracking and publishing of their diversity outcomes, investment into the mentorship of culturally diverse and indigenous junior staff and talent and tying diversity gains to leadership KPIs.

At the very least, Dr Martin hopes that the report has started some important conversations within the leadership structures of Australia’s news media landscape.

“I hope the report is generating conversations within the media organisations regardless of what their public response has been,” says Dr Martin.

“Because there clearly is a problem. And the data tells us it hasn’t improved since 2020. So overall, it would be a good idea for the media organizations to take a good look at where they need to do better in their organization and set some measurable goals for what they would like to achieve in the next couple of years, and then actually take steps towards achieving that.”

For Ash, a more diverse media means other middle eastern media personalities won’t have to struggle with the same isolation that she did.

“I do remember sitting in the Channel 10 makeup room and looking around and realizing I don’t look like these people. My experiences are not the same as these people. And the other women who I see who have the same heritage as me are always the panellists and never the host,” says London.

“The fact that I can name on one hand the other Lebanese women on commercial television is pretty indicative of the fact that the representation just isn’t there.”