Multicultural vs intercultural: Is Australia getting it right?

Australia prides itself on it’s multicultural moniker – but is intercultural awareness what we should be striving for?

The last Census conducted back in 2021 revealed that 27.6 per cent of Australia’s population were born overseas.

The Census also revealed that the top 5 languages used at home, other than English, were Mandarin (2.7 per cent), Arabic (1.4 per cent), Vietnamese (1.3 per cent), Cantonese (1.2 per cent) and Punjabi (0.9 per cent), while the top 5 ancestries were English (33.0 per cent), Australian (29.9 per cent), Irish (9.5 per cent), Scottish (8.6 per cent) and Chinese (5.5 per cent).

So what is the main difference between being multicultural and intercultural?

Multicultural refers to the coexistence of different cultures within the same space or society. The main focus is on diversity, recognising and preserving distinct cultural identities. The key idea is many cultures, living alongside one another.

Intercultural refers to the interaction between cultures, focusing on communication, understanding, and exchange. The focus is on integration and dialogue fostering connections and mutual respect across cultures. The key idea is cultures interacting, influencing and learning from each other.

Australia adopted multiculturalism as national policy back in the 1970s – with the aim to promote cultural diversity, support one’s freedom to maintain their cultural heritage, and equal opportunity. Today that looks like our many diverse communities preserving their cultural practices, languages, and religions — side by side, but not always mixing deeply.

Not too long ago Square Holes worked on a project with a major beer company on a cultural diversity piece – looking at how to better understand Asian attitudes towards drinking, ceremony and celebration. The conversations were insightful and eye opening, delving into how Australia pub culture can feel foreign and unwelcoming to different cultures who find other ways to come together with their friends and family.

The project was a prime example around how as a nation we need to work harder at incorporating intercultural perspectives across all aspects of life – including education, community, business, media and national policy.

What that could look like:

- Move beyond “food and festivals” to deeper cultural empathy and understanding.

- Create meaningful, ongoing contact and collaboration, not just parallel lives.

- Don’t just hire for diversity — build systems where diversity thrives through interaction.

- Shape public narratives that reflect an interconnected cultural identity, not just separate ones.

- Move from diversity management to active cultural engagement as a national strength.

In an SBS podcast about the importance of cross cultural friendships, Professor Catherine Gomes, who specialises in communications in diverse communities at RMIT, stated that cultural silos can stunt the experiences of new immigrants.

“In a silo you think the same way as I do. So when it comes to information and perspective about living in your destination country, whatever my friend knows is what I know. That becomes problematic because you’re not actually understanding how you’re going to be living in this foreign country.”

Arguably they also stunt the experiences of locals.

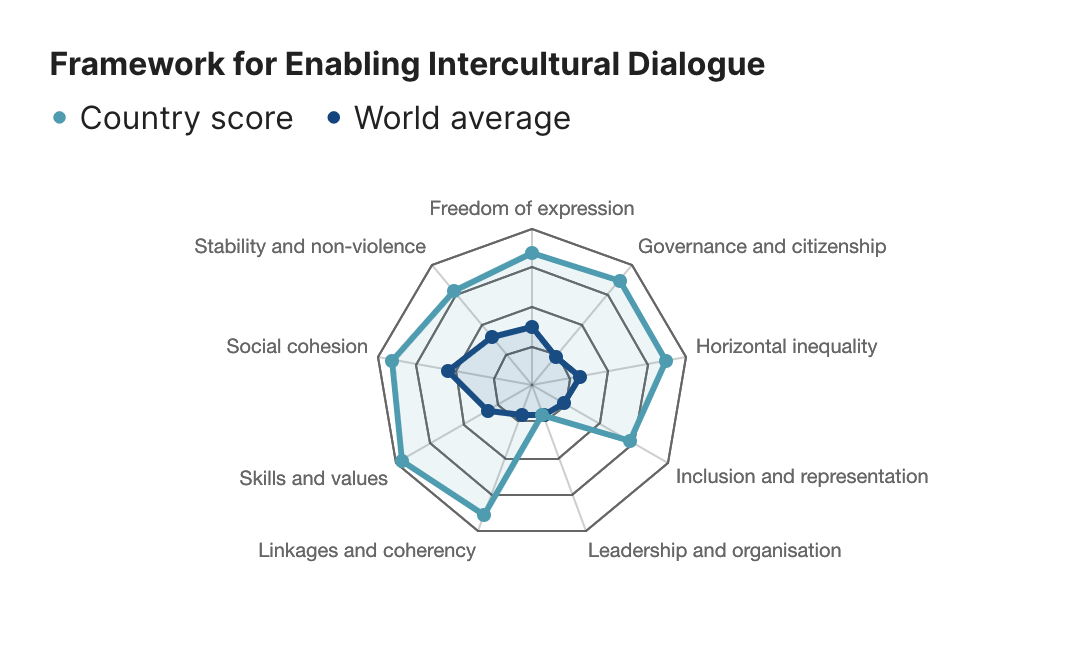

The UNESCO Framework for Enabling Intercultural Dialogue is “an integrated approach for monitoring the strength of the structures, processes, values, and skills which make intercultural dialogue effective as a tool for advancing peace and inclusion in 160 countries.”

Of the nine Framework’s domains, Australia scores highest in Skills And Values & Social Cohesion. Our problem areas are Leadership and organisation, and Inclusion and representation.

Inclusion and representation, in this instance, looks like meaningfully including and representing all groups with an interest in particular intercultural issues or dynamics for intercultural dialogues to be effective. That means that representative groups or individuals need to be included in the “planning, undertaking, or benefits of dialogue processes”, so that the intercultural dialogue is effective.

Leadership and organisation, in this context, is measured by the credibility and legitimacy of those who have established dialogue processes, as well as those facilitating them. It also includes consistency in funding and support of those processes.

Australia is undoubtedly a multicultural nation, rich in its demographic diversity and long-standing policies that support cultural inclusion. However, the real growth lies in Australia’s movement toward becoming more intercultural — where diversity is not just present, but deeply connected through shared understanding and mutual respect.