Beyond academia, the value of cultural insight and “textural gaze”

As someone who has spent his life in the so-called “ivory tower”, teaching classes in fields like sociology, communication and cultural studies, and most recently working in a university program on creativity and innovation, it has been rewarding to discover that cultural insight has become more valued in business and allied fields like leadership and strategy.

We ivory tower-types naturally assume that everyone in business or professions like city economic development is into spreadsheets, data analytics, and takes a dim view of the humanities and the so-called “soft” social sciences. But as I learnt when I gave a “thought leader” talk to several hundred delegates at a luxury tourism trade event a decade ago, people outside academia can be just as curious about what makes people tick and why people attribute certain meanings to things.

At the reception after the thought leaders panel (my talk was entitled “From Opulent to Sleek”), delegates asked me questions and made comments I didn’t often get from undergraduates. Questions like “do you use semiotics in your research?” and comments like “you are so right. Whenever I travel for my hotel manager job, I hardly ever stay in a room designed with Liberace in mind!”. (NB: undergraduates don’t often stay in luxury hotels so comparing them to delegates at Luxperience 2014 was perhaps a tad unfair).

Upon reflection I shouldn’t have been as surprised as I was by the response from the trade show delegates. After all, curiosity is curiosity, no matter your day job. But it also stands to reason that if your day job requires you to understand a subtle shift in consumer moods or requires you to invest the kind of money necessary to build a new luxury hotel, then some degree of cultural insight might be needed. Indeed, entire professional bodies have sprung up in the last decade devoted to marrying business practices with the humanities and “soft” social sciences.

One is EPIC or Ethnographic Practice in Industry Contexts. These folks run entire conferences and web workshops on topics like what anthropology and cultural studies can teach brand managers and whether tourism planners need to understand the smell and sound of their cities. These are the kind of industry personnel likely to own a copy of Christian Madsbjerg’s Sensemaking, recently reviewed by Jason Dunstone in Think!

There are several important messages in Madsbjerg’s book but one recurring theme is that our “fixation with STEM erodes our sensitivity to the nonlinear shifts that occur in all human behaviour and dulls our natural ability to extract meaning from qualitative information”. Hurray. Hopefully more students in marketing, management or tourism and events, will take the kinds of university courses I have taught over the years.

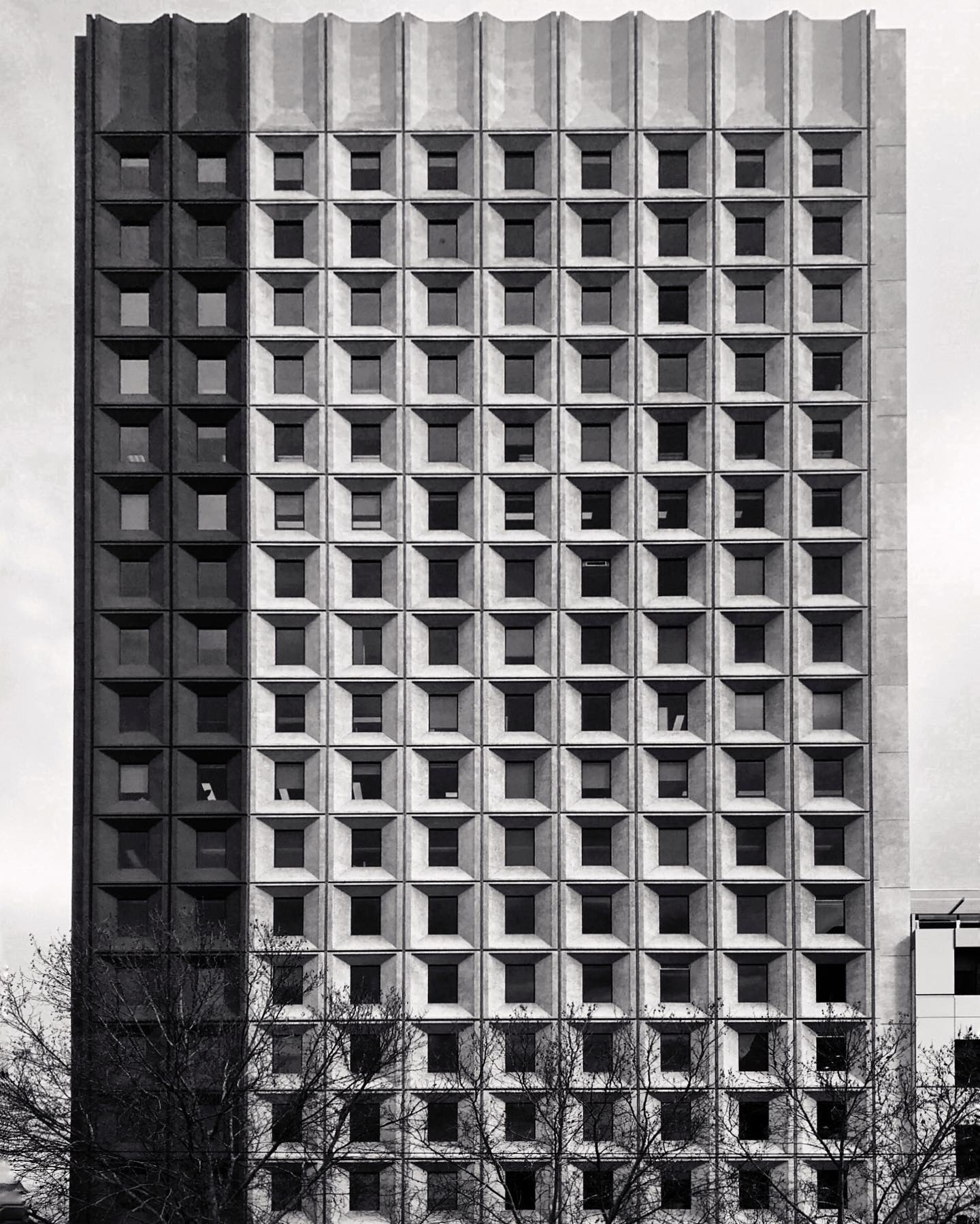

However, sensemaking is an interesting concept. Do we make sense of things consciously or unconsciously? Through our bodies or through our minds? And what about things that only appear in our “peripheral vision” or which we stumble across through serendipity? And, although I share the suspicion towards “thin data” Madsbjerg expresses (i.e., data that doesn’t put information into some type of context), I also marvel at how the Facebook algorithms correctly guess I’m likely to be interested in joining the “Brutalism Appreciation” group, the “Moss Appreciation” group, “Photos of Old Montevideo” (the city I was born in) and “Ruins of South Australia”. So sensemaking isn’t something that technical systems or Artificial Intelligence can’t perform to a degree.

What the algorithms may fail to make sense of (and here I do agree fully with Madsbjerg) is the pattern underpinning my perverse taste in Facebook groups. And this is a good point at which to segue to the title and theme of this thought piece. What this odd mixture of Facebook groups has in common is they involve a fascination with textures. The groups are participating in the application of what I call the “textural gaze”.

The surface-textures posted on these Facebook sites are varied and usually express a strong aesthetic or emotional intent on the part of the person posting. Thus, for example a common theme in the Brutalist architecture group is concrete that is stained or changed colour due to age or climate. But these textural qualities are often celebrated rather than derided. And group members often have strong opinions about the merits of painting, rendering, renovating or pressure cleaning, the surface in question. The members take the “Appreciation” in the name “XXX Appreciation Group” very, very seriously.

Now what people are posting in “The Moss Appreciation” or “Corrugated Iron Appreciation” Facebook Group may strike you as banal. But as we live much of our life through encounters with various surfaces and interfaces, arguably, all forms of textural curation matter more than we realise. An article in The Guardian went as far as to suggest that in the case of Brutalist architecture, a style that provokes strong emotions and which has been blamed for many social ills, Instagram has probably saved more buildings destined for demolition than any heritage body or urban activist group.

However, I would like to make a bolder claim than social media has saved a few buildings: namely, I want to claim that possessing a feel for the textures of the world is a useful tool whatever your day job. Whether you are in the creative industries, a professional in design or heritage, a place manager or tourism branding expert, or simply someone who is passionate about their town or neighbourhood, it doesn’t hurt to possess a textural imagination or to cultivate a textural approach to things.

The anthropologist Kathleen Stewart has suggested that the textures of the world require “attunement” – which is just a fancy word for mindful engagement with something. Occasionally, the visitor or newcomer can glimpse or intuit something profound about a place. This is why travel writers and skilled street photographers sometimes capture things missed by those who live there. But being attuned to things is more than intuition or lucky guesses.

Attunement often requires patience, repeated engagement with something, and knowing how to employ all the senses, including kinaesthetic sensation (i.e., the world often looks and feels differently if we are walking, running, climbing, swimming, cycling, driving, or better still standing or sitting still). Textures also force us to develop good “bullshit detectors” and check our capacity for hubris. It forces us to ask: have I paid sufficient attention to the “fine grain” of something?

Developing a feel for the textures of the world is therefore not about following ready-made formulas. Textural insights might be hard to convert into bullet points in a PowerPoint presentation. But, if you are a consultant, developing a feel for texture may involve thinking twice before “cutting and pasting” from a report prepared for another client. And to return to where I started, namely, how the worlds of academia and business or city economic development often seem overly separated, what if the key to building bridges between different sectors is finding common threads and making unexpected conversations possible?

There is no single model of “how to be a good or effective texturalist”. Indeed, due to very nature of the ethos, texturalism could well be about practising one’s craft with a degree of humility and recognition that the world is so texture-rich we can’t understand or master all textures. The textural ethos also suggests the need to develop an empathy for the thing we are working with – be it yarn, wood, soil and vines (one of the examples covered in Madsbjerg’s Sensemaking), or, for that matter, different types of consumers and varieties of mainstreets/retail precincts.

But I fear I am beginning to weave a new narrative. And a good texturalist also needs to know when to stop.

Author Dr Eduardo de la Fuente is a peri-metropolitan writer and researcher specialising in culture, economy, space and place, and the ‘textures’ of everyday life. In addition to his role as Adjunct Senior Lecturer in Justice and Society, Eduardo is a Fellow of the Institute for Place Management (Manchester Metropolitan) and a Faculty Fellow of the Yale Centre for Cultural Sociology. In 2020, he and Ariella Van Luyn (UNE) published the co-edited volume Regional Cultures, Economies and Creativity: Innovating through Place in Australia and Beyond.