Is social media behind the current wave of adult ADHD diagnosis?

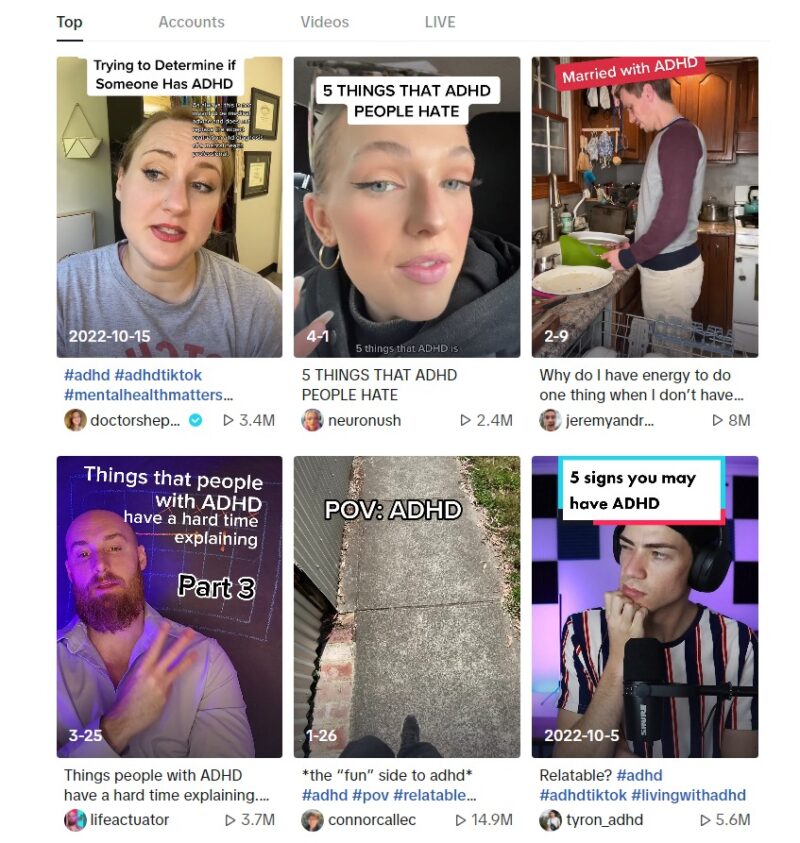

If you have been on social media in the past year, chances are you’ve come across the #ADHD content that has flooded TikTok and Instagram since the onset of the pandemic. Raging from influencer led videos, to infographics from registered psychologists (and everything in between) this content ranges in tone from informative, to humorous, to anecdotal, to diagnostic.

When done correctly, these short viral videos and graphics spread ADHD awareness, build community, and help to destigmatise mental health. However, they can also work to perpetuate stereotypes, ignore comorbidities and nuance, and are helping to fuel a mental health access crisis.

The big question is, can platforms built for dance videos and pretty pictures become a significant source of health information – or is the risk of misinformation too great?

ADHD or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is a condition commonly understood to start in childhood that affects behaviour. ADHD symptoms fall into two distinct categories – inattentiveness, and hyperactivity and impulsiveness, and can include things like trouble concentrating, excessive talking, or constantly moving from task to task. To formally diagnose ADHD, a specialist assesses you against a strict checklist of symptoms along with your symptomatic history. It’s key to note that having one or two traits doesn’t necessarily mean you have ADHD.

In 2022, prescriptions for ADHD medications in Australia exceeded 3.15 million – two and a half times the number of prescriptions issued just four years earlier in 2018. At the same time #ADHD videos on TikTok have received over 2.4 billion views, with ADHD influencers sharing everything from relationship advice to symptoms to look out for.

And while many people are applauding the sudden spotlight on misrepresented condition, others are warning of the danger in sourcing health information via social media.

In a study conducted in March 2022 and published in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry it was uncovered that a high prevalence of misinformation about ADHD was being spread in TikTok videos.

In an article posted on PsyPost, study author and geriatric psychiatrist and sleep disorder medicine fellow at the University of British Columbia, Anthony Yeung warned that misleading information could potentially result in an increased risk for overdiagnosis or misdiagnosis.

“In the past 2 years (in particular since the start of the pandemic), many doctors are noticing an increase in patients showing up to their offices wondering if they have ADHD,” said Yeung.

“We think TikTok has been at least partly responsible for this increased awareness of ADHD. The hashtag #adhd is the seventh most popular health hashtag on the platform, and there is a large ADHD community on the platform as well.”

Yeung goes on to explain that this increased awareness is a doubled-edged sword, as alongside stigma and myth busting, there is the potential for misinformation to spread.

“Social media and health misinformation is an area that requires urgent investigation. We need to understand how not just TikTok, but also other social media platforms might rapidly propagate misinformation, and the implications it may have on public health and healthcare.”

But for the less visible ADHD and ADD community members, like 35-year-old leather worker Elysia Bennet, social media has helped her to first seek, and then come to terms with her diagnosis.

“It (the role social media played) was huge. You have so much access on (for me) Instagram. I don’t do TikTok, but I just found some pages that were ADHD folks sharing their experiences and information they’ve gathered over the years. I found that extremely helpful and I know it was just nice to be able to relate and not feel alone in it because there’s really not a lot of direction of where else I could find that information,” says Bennett.

Professor Alasdair Vance, Associate Professor of Child Psychiatry, Paediatrics Royal Children’s Hospital agrees that social media can be a powerful education tool but warns against people using it to self-diagnose.

“I think that social media can be very helpful if it’s educative in terms of raising issues for further consideration. But it is wholly inadequate in terms of the diagnostic process. And wholly inadequate in terms of setting up a holistic management plan,” says Professor Vance.

“What I mean by that is that ADHD, in essence is a developmental disorder. Biologically in terms of neurodevelopment as well as psychically in terms of psychological development, as well as holistically, social development, spiritual development, there’s a delay, but it is more than neurodevelopment. So, medication alone is never the solution.”

Access to ADHD medications have become much easier to obtain during the pandemic, as social distancing measures removed legislative barries that previously restricted remote provides from prescribing controlled substances and resulted in a boon of ventured-backed telehealth startups.

At the same time the “striking overlap between ADHD symptoms and garden variety ‘pandemic brain’ only compounds common misunderstandings of the former.” Which means that the collective trauma of the pandemic has impacted how we focus and attempt to adhere to pre-covid workflows. As the pandemic has worn on, these issues have only become more pronounced, with people drawn to self-pathologising in the face of a great unknown.

“I think that anyone can be inattentive. Anyone can have troubles encoding information, holding information in mind, or retreating information, particularly if they’re stressed,” says Professor Vance.

“ADHD really is evident because it’s not situational. It’s evident in more than two settings. And it’s present for months on end, at least six months. And it’s noted usually by more than one informant, which again, I think is a critical problem with adult practice.”

Add to that the fact that historically research revolving around ADHD has focused primarily on how it presents in young males, leading to the chronic underdiagnosis of women, non-binary folk, and people of colour – it’s no wonder that people are self-diagnosing through social media.

In Australia this has resulted in a rising mental health access crisis, with people seeking diagnosis waiting for up to two years and spending thousands of dollars in the process.

Elysia says that this is another reason social media is important – to prepare people for the arduous process of seeking a diagnosis.

“It is a really lengthy, hard process which isn’t really designed for ADHD folks because we obviously struggle with booking appointments, and then making it to those appointments. The process is really bad,” says Bennett.

“So, I think it’s good that you can access the information on social media, that prepares you for, hey it’s going to be a rough trot to get to your diagnosis. But at least you can be prepared and know it’s not just you. Everyone has to go through that process.”

While Professor Vance agrees that there is currently a trend of overdiagnosis of mild cases, but that there is a critical underdiagnosis of the more serious cases, “where it’s ADHD plus bipolar, depression, psychosis, or substance abuse.”

But Professor Vance feels that this is owing to the current model of our health system.

“I do think we need to get away from this capitalistic, quick business model of health. We’ve got to argue and fight for a far more holistic model. And the problem at the moment is the quick questionnaire, the quick interview, the quick script is just not helping our community. Cause that’s not really health.”

For Elysia, she argues that this wave of people seeking diagnosis is a positive thing. Especially if those who have been traditionally ignored by the health system can finally find some support.

“It’s a lot more common than people realize. Like I know a lot of people are saying ‘oh everyone’s got ADHD now.’ But it’s actually more common than we realise, and we need to go with the flow of that and let people get their diagnosis and try to better their lives,” says Bennett.