Four factors that will shift the Voice referendum towards no change

With all the discussion around the Voice referendum coming up at the end of this year, it can be easy to be perplexed by the debates from either side. While the outcome may seem quite logical, there are many opposing forces that will have a great influence on the outcome. Likely it will not be as anticipated.

The Indigenous Voice to Parliament Referendum is a vote on whether Australian voters want an alteration to the Constitution that establishes an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. What is evident is that Australia is divided on this matter and there are facts and misinformation flying thick and fast.

The last time a referendum was held in Australia was back in 1999.

This referendum requires voters to choose either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on the following statement:

‘A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?’

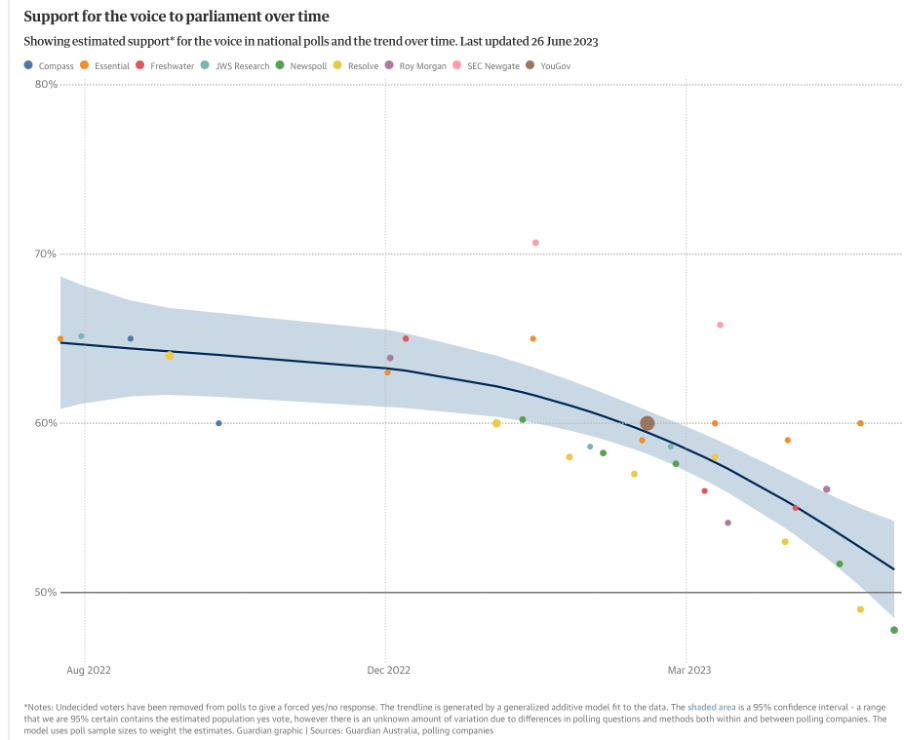

Polling is illustrating that the majority will vote ‘yes,’ yet there is no guarantee, as polls can lie, and indication across tracking is that support is in significant decline.

For a referendum to pass, a national majority of voters, as well as a majority of voters in a majority of the states (at least four states) must vote ‘yes’ to the change.

In December 2017 Australia had a postal vote on the plebiscite for gay marriage, in which 80% of Australian adults voted, with 7,817,247 (62%) responding ‘yes’ and 4,873,987 (38%) responding ‘no’ (More >). In retrospect the vote to allow ‘same-sex couples to marry’ seems quite logical, and even inevitable, particularly as Australia was somewhat of a laggard in making such an important change. Much of the developed world had already made such a change (More >). It was a tad embarrassing.

Importantly the last time a referendum was held in Australia was back in 1999. Of the 44 referendums in Australia from 1906 to 1999 only eight have been successful (i.e. 36 of the 44, meaning 82% have not been successful). The marriage equality plebiscite was successful, but only two of the four in Australia since 1916 have been. The odds are stacked towards the status quo. (More >)

It can be easy to take ‘success’ in such votes for granted. “All my friends and family agree with me, and of course we are normal, so success is guaranteed.” But, there are few guarantees in life, and referendums have a high chance of failure.

With this is mind, I reflect on three factors that further exaggerate the challenge.

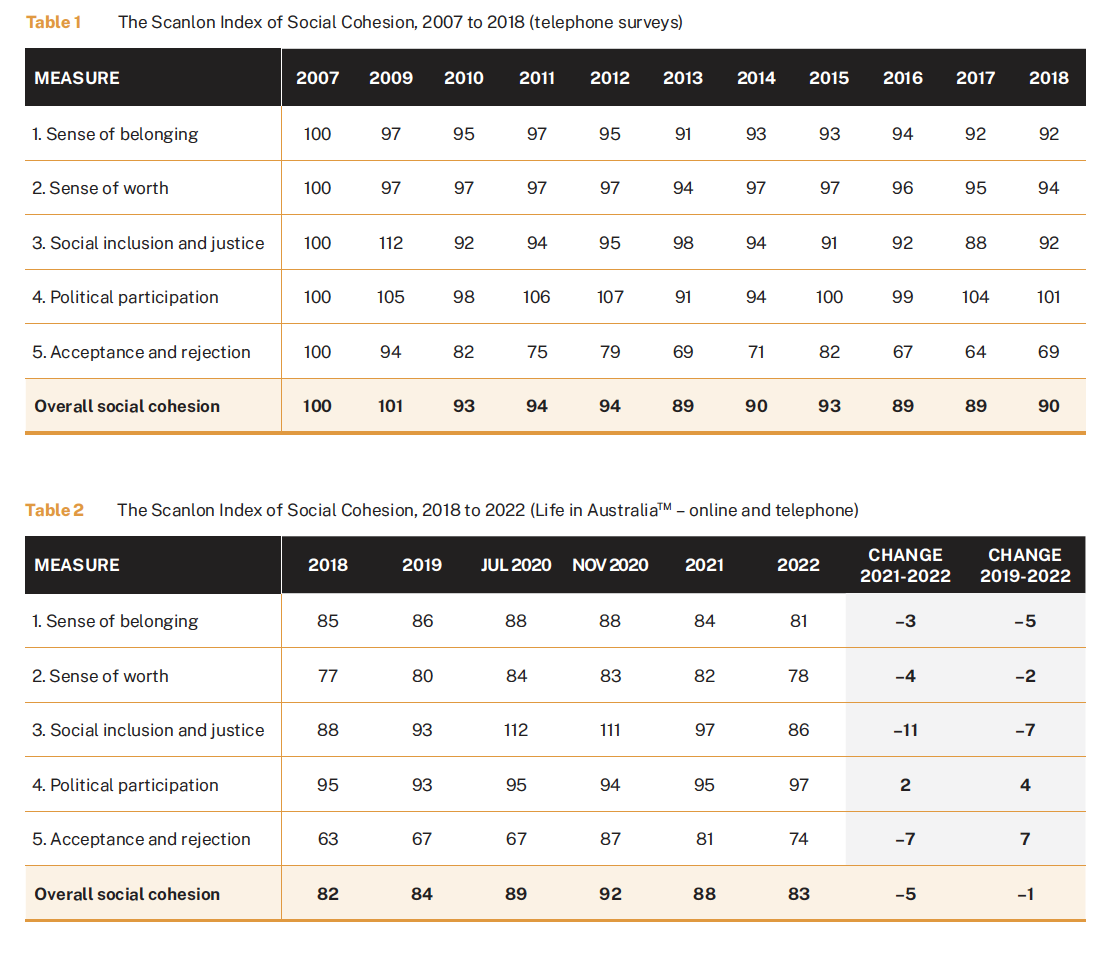

Social cohesion is weakening

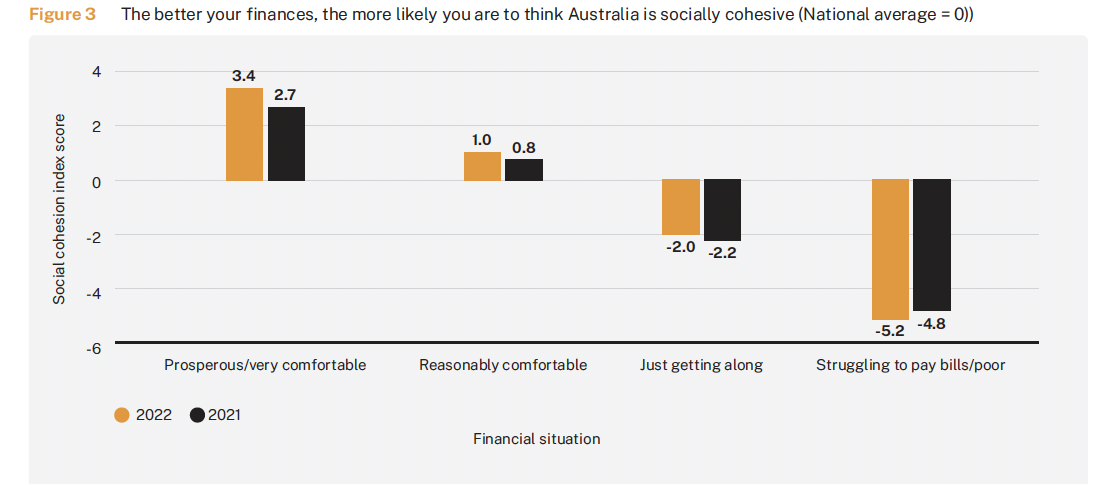

A survey conducted in 2022 led by Australian National University researcher James O’Donnell illustrates that while Australian performed generally well during the pandemic, and our country is a fairly egalitarian place, the inflation shock and threat of economic issues were impacting our sense of social cohesion.

Overall the past 15 years social cohesion in Australia had been in decline, so the pandemic led improvement in 2020 to 2021 was a pleasing bounce back to previously higher levels.

Further to this, the research also indicates that as Australia’s personal financial comfort declines, so too does the sense of social cohesion. In this time of recession threat, inflation and cost of living pressure, there is downward pressure on social cohesion. In times of declining security the community can feel a declining level of social cohesion and comfort in retaining the status quo.

Social proof and confirmation bias

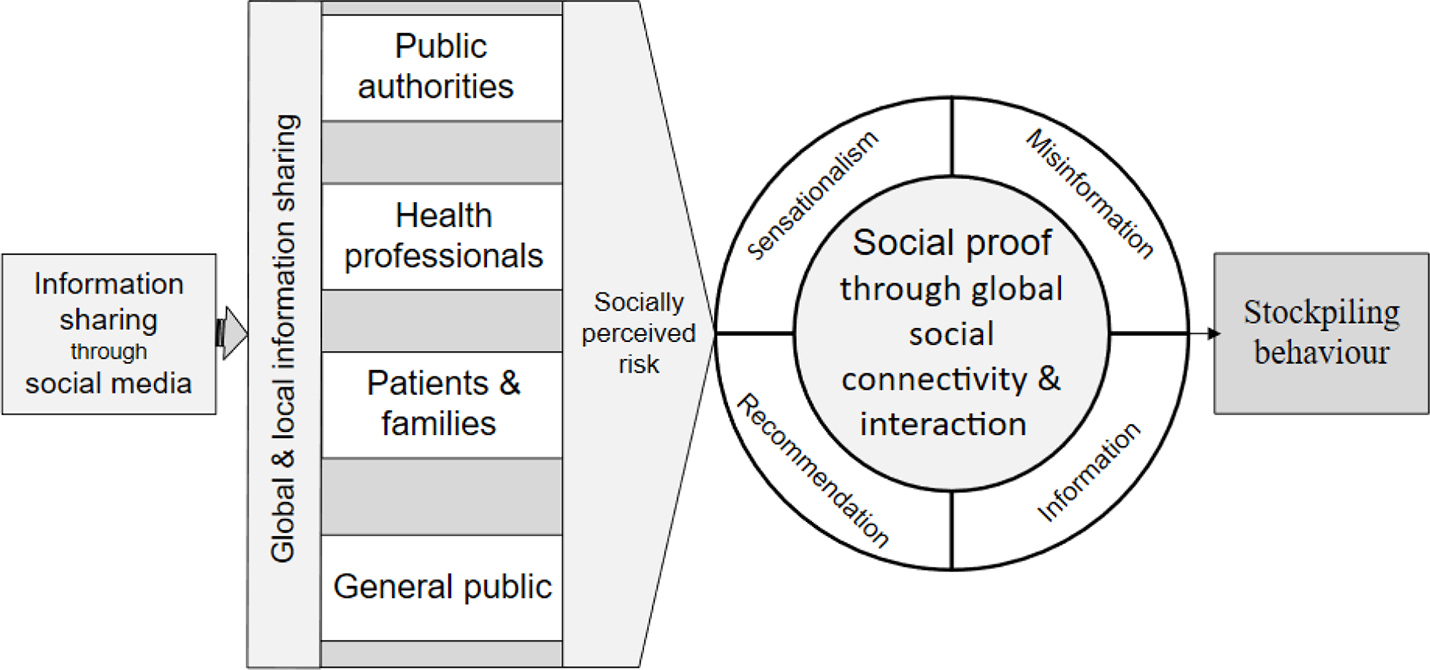

The values of our time come from social proof, the psychological tendency for people to seek conformity to ensure they behave in a socially acceptable manner. It makes people feel confident, provides a sense of belonging and sharing commonality. Groups of friends, family and work colleagues find a level of social proof and normalised opinion, that may or likely will not align with that of other aligned groups.

Friends and family reinforce the group norm, even our social media connections can be more so aligned than not, and tendency can be to ignore different perspectives. Confirmation bias means that human nature is to seek information that confirms our existing views and ignores any counter evidence.

Misinformation and confusion

Knowledge is power, yet it can be hard to shift perspectives from ‘yes’ to ‘no.’ What is more realistic is how to guide those open to new information from ‘I don’t know’ (or ‘yes’ or ‘no’ but not quite convinced) to be better informed. In the current Voice referendum, there is an undecided vote of around 20% with a large amount of power, depending on which way they cast their vote. Clarity of information is the optimal way to move the vote in the right direction, yet the tendency can be to fight with misinformation and fear. Sadly fear of change is a major influencer in seeking comfort in the status quo.

We are more so history ostriches than emus

The ostrich effect is the tendency to avoid dangerous or negative information by simply closing oneself off from this information. Australians can be ostrich-like when it comes to Australia’s history.

Earlier this year I spent a few weeks in the UK, Latvia and France. One of the critical observations was how important history was to the identity of the cities large and small I visited. From the steel manufacturing roots of Sheffield, to the narrative of invasion, mistreatment and strength of Riga. From the historical Blue Plaques of London, to the unavoidable architecture, galleries and museums of Paris. History fundamental in the sense of identity and pride.

Australia is a comparatively young country, if we exclude our 65,000+ First Nation history, and as a country we can have a reluctance to celebrate our history, at least partly stemming back to to a history of shame, and lack of willingness to take ownership of the associated ramifications of neglecting and ignoring our rich history, First Nation and otherwise.

“Aboriginal Australians are descendents of the first people to leave Africa up to 75,000 years ago, a genetic study has found, confirming they may have the oldest continuous culture on the planet.” Australia Geographic, September 2011, Read more >

In early 1836, nine ships accommodating 636 people in total set sail for South Australia, with Governor Hindmarsh arriving on 28 December 1836 to proclaim the province of South Australia, the only Australian colony which did not officially take convicts. Australia’s early settlers claimed the land terra nullius, a term meaning ‘nobody’s land.’ An outcome of terra nullius was around 150 reported massacres of Indigenous Australians by European settlers. Along with disease and other factors had a decimating impact on the First Nation population. The last reported massacre of Indigenous Australians was in 1930. The right to vote in Federal elections came in 1962, and the last State to allow Aboriginal people to vote was Queensland in 1965 (around 38%, of Australia’s First Nation population). The stolen generation remained into the 1970’s.

From 1971 court cases disputing terra nullius failed to accept native rights, and it wasn’t until 1992, after 10 years of Queensland Supreme Court and the High Court of Australia, the latter court found in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (“the Mabo case”) that the Mer people had owned their land prior to annexation by the colony of Queensland (1872–1879). It wasn’t until 2008 that Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said ‘sorry,’ for Australia’s poor history of settlement in Australia and impact on the native population.

In recent research we conducted about education in schools about First Nation history, most teacher respondents were lacking in historical understanding and empathy. While they acknowledged progress was being made in recent years, there was often awkwardness around accepting and fears about communicating the complex history respectfully.

…

From my personal perspective, the Voice referendum is a huge opportunity to place a critical line in the sand. To acknowledge and accept our history, at times worthy of much pride and other times much shame. The Voice will unlikely be ‘the’ change to overcome actual, significant and frightening imbalance. For example, an estimated gap of approximately 17 years between Indigenous and non-Indigenous life expectation in Australia. Yet, it is an important next BIG step, to learn from the past and put critical structures in place to do much better in the future.

To me, the Voice is about respect and empowerment.

It is also about tangibly and systematically acknowledging Australia’s dubious history, and move forward with a greater sense of reflection. As those who do not learn from the past are destined to repeat it.

There is also a niggling pestering thought in my mind that if we can put this important line in the sand, we can overcome many of the wider shortcomings of Australia. For example, Australia ranks comparatively low globally on innovation. Ranking 25th on a global innovation index (and declining – more >). Perhaps at least part of this is due to not valuing and ignoring our history. It would be a shame to not see the critical change that is needed for respect and progress.

So, if you would like to see the ‘yes’ vote win in this year’s referendum, do not be apathetic, play your role in clearly educating the uninformed and encourage others not to be led by fear and temporary financial uncertainty as an excuse for no change. In such a big historical change, being aware of the hurdles to change is worth considering, as there are many opposing forces pulling against it.

You may also find the following of interest …

Are you unconsciously racist?

Are ‘people like you’ the problem?

Are we the lucky country yet?