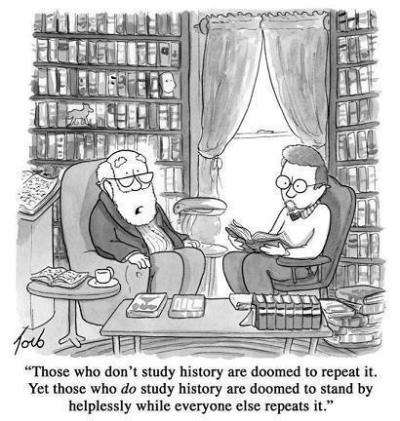

A reflection on history education

The single most important thing we can give our children and young people is a good education. Be this as parents, or the wider community and government, education is the fundamental way our society makes progress in the future. A critical question can be, what defines a good education?

This is a complex question, with a multitude of answers, including to get a good job, and to be a good human. This week Square Holes started a research project in relation to teaching history in schools, which got me thinking about the role learning about the past has for our young people in pursuit of a good future.

“A generation which ignores history has no past and no future.”

Robert Heinlein, American author (1907-1988)

There are so many topics that need to be covered in the primary and secondary school curriculum, so it is interesting to reflect on the value our community and government places on history.

Earlier this year I spent a few weeks in the UK, Latvia and France. One of the critical observations was how important history was to the identity of the cities large and small I visited. From the steel manufacturing roots of Sheffield, to the narrative of invasion, mistreatment and strength of Riga. From the historical Blue Plaques of London, to the unavoidable architecture, galleries and museums of Paris. Very old and entrenched history, fundamental in the sense of identity and pride.

Australia is a comparatively young country, if we exclude our 65,000+ First Nation history.

“ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS ARE descendents of the first people to leave Africa up to 75,000 years ago, a genetic study has found, confirming they may have the oldest continuous culture on the planet.”

Australia Geographic, September 2011, Read more >

In early 1836, nine ships accommodating 636 people in total set sail for South Australia, with Governor Hindmarsh arriving on 28 December 1836 to proclaim the province of South Australia, the only Australian colony which did not officially take convicts. So, a history of less than two hundred years, if we exclude our First Nation history, is comparatively young relative to our mother country counterparts.

Reality is that Australia does have a long history.

Australia’s early settlers claimed the land terra nullius, a term meaning ‘nobody’s land.’

An outcome of terra nullius was around 150 reported massacres of Indigenous Australians by European settlers. Along with disease and other factors had a decimating impact on the First Nation population. The last reported massacre of Indigenous Australians was in 1930. The right to vote in Federal elections came in 1962, and the last State to allow Aboriginal people to vote was Queensland in 1965 (around 38%, of Australia’s First Nation population).

The stolen generation remained into the 1970’s.

From 1971 court cases disputing terra nullius failed to accept native rights, and it wasn’t until 1992, after 10 years of Queensland Supreme Court and the High Court of Australia, the latter court found in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (“the Mabo case”) that the Mer people had owned their land prior to annexation by the colony of Queensland (1872–1879).

It wasn’t until 2008 that Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said ‘sorry,’ for Australia’s poor history of settlement in Australia and impact on the native population.

Australia’s history is much wider than our First Nation history, our reluctance to celebrate our history may stem back to a history of shame, and lack of willingness to take ownership of the associated ramifications of neglecting and ignoring our rich history, First Nation and otherwise.

In recent research we conducted about education in schools about First Nation history, most teacher respondents were lacking in historical understanding and empathy. While they acknowledged progress was being made in recent years, there was often awkwardness around accepting and fears about communicating the complex history respectfully.

Reflecting back on my trip to the UK earlier this year, Australia’s history was quite prominent in galleries and museums in London, e.g. in the British Museum and the Tate Modern. The depictions were often negative as to mistreatment by the British Empire and Australians. Travelling around the UK to places like Leeds, building developments were more so about modernising historical buildings, than demolishing and replacing with new. In larger cities such as London and Paris great care was taken to preserve historic architecture and enhance for the future.

Australia can have a tendency to lack valuing history, to demolish or leave a slim façade of the exterior of the building. Or acquiring homes nearby new highways, to demolish for construction space. Rather than being more cautious about what is destroyed and the history worth retaining. With the continuous removal and ignoring of history it is not surprising that our young people, their parents, schools and the wider community place limited, if any value.

Australia ranks comparatively low globally on innovation. Ranking 25th on a global innovation index (and declining – more >). Perhaps at least part of this is due to not valuing and ignoring our history.

History is history, but if we don’t recognise and learn from it, progress is hard.