Is AI here to steal our jobs?

Society is currently in the golden age of progress in artificial intelligence, with new advancements developing quicker than we have time to reflect on the potential consequences.

We have AI creating artworks, writing poetry, producing storyboards for feature length films, generating pitch perfect essays and even soon to be flying warplanes.

The conversation around tech developments like ChatGPT and DALLE-2 have reached such a fever pitch that even rock greats like Nick Cave are chiming in.

In a recent edition of his confessional newsletter, The Red Hand Files, where fans write in their burning questions, Nick was faced with a ChatGPT penned tune, written ‘in the style of Nick Cave’.

Along with his immediate review of the song (“This song sucks”), Nick went on to voice a growing collective unease with how rapidly these new technologies are evolving.

He wrote, “I understand that ChatGPT is in its infancy but perhaps that is the emerging horror of AI – that it will forever be in its infancy, as it will always have further to go, and the direction is always forward, always faster. It can never be rolled back, or slowed down, as it moves us toward a utopian future, maybe, or our total destruction.”

It’s an opinion shared (though perhaps only in jest) by OpenAI (the company behind ChatGPT) CEO, Sam Altman, when he joked at a conference in 2015, “AI will probably most likely lead to the end of the world, but in the meantime, there’ll be great companies.”

The idea that robots are here to steal our jobs is not a new concept. In an opinion piece for The New York Times, columnist Paul Krugman writes:

“People have been asking that question for an astonishingly long time. The Regency-era British economist David Ricardo added to the third edition of his classic “Principles of Political Economy,” published in 1821, a chapter titled “On Machinery,” in which he tried to show how the technologies of the early Industrial Revolution could, at least initially, hurt workers. Kurt Vonnegut’s 1952 novel “Player Piano” envisaged a near-future America in which automation has eliminated most employment.”

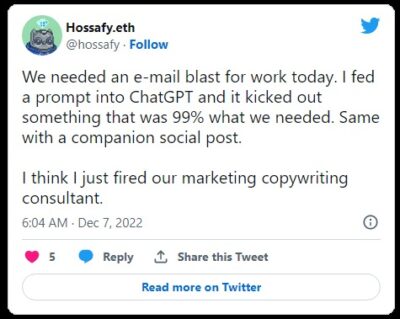

His article surmises that, in the past, job loss to technology has tended to involve primarily those roles that focus on manual labour. Krugman adds that with the introduction of AI like ChatGPT, society could now be grappling with technology coming for the jobs of “knowledge workers” (a term for people engaged in nonrepetitive problem solving). Which means that we are potentially looking at a future where tasks such as data analysis, research and report writing are conducted wholly by machines.

For the as yet uninitiated, ChatGPT is a program designed to carry out natural conversations, with the OpenAI website, stating that the program can, ‘answer follow-up questions, admit its mistakes, challenge incorrect premises, and reject inappropriate requests.’

And while the general public have been enjoying putting the new tech through its paces with university assignments, and non-sensical bible verses – concerns about the potential of the program to have a devastating impact on our work force have come from an unlikely source – ChatGPT itself.

In a column written for global flagship Semafor, with the prompt, ‘Write an article about the potential and pitfalls of AI?’, the tool penned that, “One of the biggest concerns is the potential for AI to replace human workers and lead to job loss. As AI algorithms become more advanced, they may be able to perform tasks that were previously performed by humans, which could result in job losses in certain industries.”

It isn’t the first article penned by ChatGPT since the technology was launched, with everyone from New York Magazine, to Sky News and the Guardian testing out the potential (and limitations) of the software.

But how soon before an industry already stretched to its breaking point starts cutting even more journalists in favour of machines?

Jessica Sier, a journalist at The Australian Financial Review has written about how the bot can be used by skilled workers to automate parts of their jobs. She largely sees only the positive in the use of ChatGPT in her field.

“Regarding journalism, I think this technology is disruptive. But it’s also a tool that can free up reporters to concentrate on managing complex people-types and abstract sourcing, which is something I welcome. Journalism at its best is when it’s original and tells a great/important story. I don’t think AI can replace those elements,” says Sier.

As to whether the technology is progressing faster than our ability to consider and mitigate the ethical consequences, Jessica believes that society as a whole is much shrewder about how technology works (and doesn’t) than past generations.

“I think the unbridled spread of social media taught humanity something about how technology can influence people in a damaging way. As such, I think the digital literacy of people in modern societies has improved markedly. I think younger generations are much more aware of how technology works, how network effects form, and are developing a finer sense of how to distinguish misinformation,” says Sier.

“I speak regularly with people developing technology for profit now, and the lion’s share of them are keenly aware of the ethical implications of what they built. No one wants to build a rampant monster like Facebook again!”

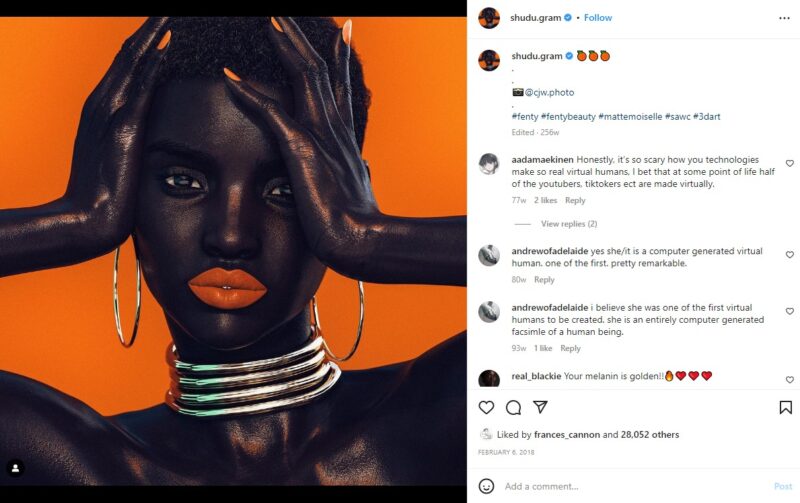

Another industry rubbing up against the ethical ambiguity of AI technology is the modelling industry.

In 2017, former fashion photographer, Cameron-James Wilson created virtual model Shudu from their bedroom using a program called Daz 3-D. Since then, Shudu has amassed over 239K followers on Instagram, featured in Vogue and Womens Wear Daily magazine, fronted campaigns for Balmain and Ellesse and has been retweeted by pop star Rihanna’s Fenty Beauty account.

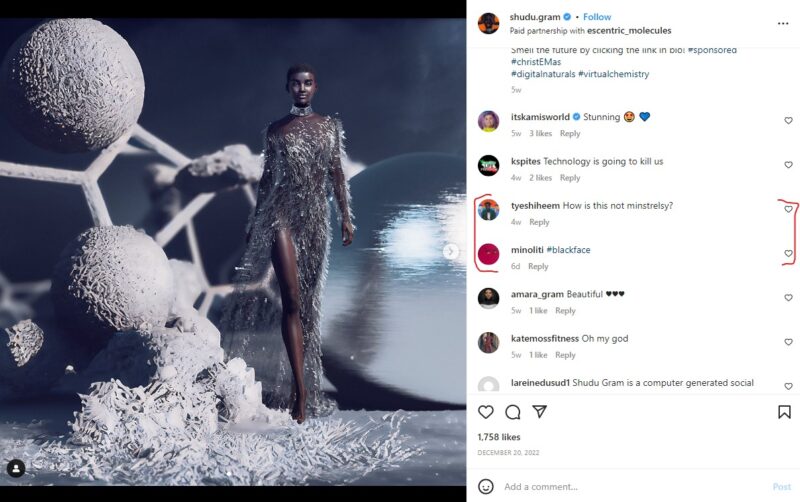

The popularity of Shudu prompted Cameron-James to launch the world’s first all-digital modelling agency, but there has been intense criticism levelled at the white creator for profiting off of the image of a black woman and taking that money out of the pockets of WOC working in the industry.

In an interview with Harpers Bazaar, Cameron James rejected these claims, stating:

“As a photographer, I work with lots of different people all the time, real people that have inspired her. At the end of the day, it’s a way for me to express my creativity—it’s not trying to replace anyone. It’s only trying to add to the kind of movement that’s out there. It’s meant to be beautiful art which empowers people. It’s not trying to take away an opportunity from anyone or replace anyone. She’s trying to complement those people.”

As Shudu has grown as an online influencer and personality, Cameron James continues to be called out via his creation’s Instagram page, with one commenter writing “how is this not minstrelsy?”, and another tagging “#blackface”.

In an interview with Time magazine , ChatGPT warned, “It’s important to remember that we are not human, and we should not be treated as such. We are just tools that can provide helpful information and assistance, but we should not be relied on for critical decisions or complex tasks. … You should not take everything I say to be true and accurate…”

In our own interview with the bot, ChatGPT cautioned that humankind may not have an adequate grasp of the ethical ramifications of this evolving technology.

“While there is a growing awareness of the potential ethical implications of AI, there is still much work to be done to ensure that its development and deployment are guided by ethical principles and values. Many of the ethical questions posed by AI are complex and challenging, requiring interdisciplinary approaches and ongoing dialogue and collaboration among stakeholders. It is important for individuals and organizations involved in the development of AI to be proactive in considering and addressing ethical issues, and to engage in ongoing reflection and discourse to ensure that AI is developed and used in ways that align with human values and principles.”

However, as we all know, “human values” can vary depending on the human in front of you. And while curiosity is driving the development of AI currently, it won’t be long before capitalist ideals sneak into our use (and potential abuse) of this technology – where efficiency and cost effectiveness rule over human interest.

At least, according to Nick Cave, AI will always pale in comparison to real human experience.

“Songs arise out of suffering, by which I mean they are predicated upon the complex, internal human struggle of creation and, well, as far as I know, algorithms don’t feel. Data doesn’t suffer. ChatGPT has no inner being, it has been nowhere, it has endured nothing, it has not had the audacity to reach beyond its limitations, and hence it doesn’t have the capacity for a shared transcendent experience, as it has no limitations from which to transcend,” Cave writes in the Red Right Hand Files.

“ChatGPT’s melancholy role is that it is destined to imitate and can never have an authentic human experience, no matter how devalued and inconsequential the human experience may in time become.”