Giving Aboriginals a Voice / Vote

As we head towards the Aboriginal Voice to Parliament Referendum tomorrow, I have been reflecting on our history and the lessons we can learn from the ‘Yes’ ‘No’ debate over the past months, and our history of recognising and respecting Aboriginal people. While progress is ever being made, we haven’t always seen the best side of Australia and Australians during 2023, with racism, ignorance and division abundant.

Changing our constitution for First Nations

On 27 May 1967 an Australian Referendum was held, which stipulated whether two references in the Australian Constitution, which discriminated against Aboriginal people, should be removed.

The sections of the Constitution under scrutiny were:

- The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to:-

…(xxvi) The people of any race, other than the Aboriginal people in any State, for whom it is necessary to make special laws. - In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, Aboriginal natives should not be counted.

The removal of the words ‘… other than the Aboriginal people in any State…‘ in section 51(xxvi) and the whole of section 127 were considered by many to be representative of the prevailing movement for political change within Indigenous affairs.

Section 127 prevented the inclusion of Aboriginal people in the official population for constitutional purposes, i.e. their population would not be included in the calculation of the number of seats to assign for each state or in the determination of tax revenue. The section did not prevent the Bureau of Statistics from counting or collecting other information about Aboriginal people. From 1911 to 1966 the Bureau had collected information about Aboriginal Australians, however this was published separately to the general population. As such, while the inclusion in the general population was important symbolically, the change did not directly improve the information available to government.

The response was an almost unanimous ‘YES,’ with 91% of voting Australians in the affirmative.

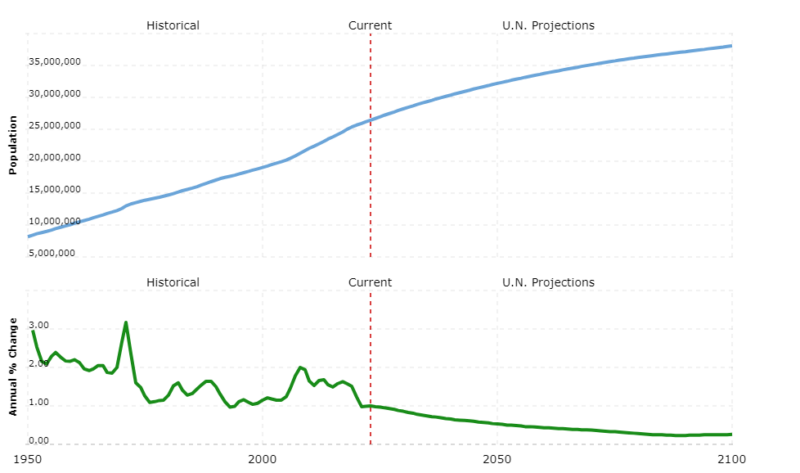

With the benefit of hindsight, it all seems quite logical to make such changes to our constitution. Australia’s population has grown from around 12 million to 26 million, and we are more sensitive of the cultural diversity of our country. Yet this was only a few years after Australia legislated to give Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples the right to vote.

Basic right to vote

Before Federation Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had varied voting rights.

While Aboriginal men could vote in Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia, it took until 1896 for Tasmania to give Aboriginal men the franchise. In 1895 South Australia gave equal voting rights to men and women, including Aboriginal women. Laws that stopped Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from voting were introduced in Queensland (1885), Western Australia (1893) and the Northern Territory (1922). The Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 gave all men and women around Australia the right to vote. But it excluded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples unless they already had the right to vote before 1901.

In Queensland Aboriginal people had been unable to vote since the late 1800s, and this restriction included Torres Strait Islander peoples as well from 1930 onwards. In the Northern Territory, most Aboriginal people were declared ‘wards of the state’, meaning they couldn’t vote. In Western Australia, the Natives (Citizenship Rights) Act 1944 allowed Aboriginal people to vote only if they could speak English, had ‘industrious habits’ (worked hard) and didn’t have certain medical conditions.

Many had to show they were no longer part of their own community, and these regulations were referred to as the ‘dog-collar act’ or ‘dog-act’. This was because these laws were offensive to Aboriginal identity and limited what Aboriginal people could do.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activists such as Joe McGinness, Oodgeroo Noonuccal (formerly Kath Walker), Dulcie Flower, Doug Nicholls, Pearl Gibbs, Faith Bandler and George Abdullah opposed these laws. They set up groups such as the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement (FCAA) to fight for voting rights and other issues.

The campaign of the FCAA and other groups led to the Australian Government setting up a select committee to investigate Aboriginal voting rights in 1961. It interviewed 324 people, and almost half of these were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The committee found that 30,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were not allowed to vote in the Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland. In response, the government introduced a Bill to ‘give to Aboriginal Natives of Australia the right to Enrol and to Vote as Electors of the Commonwealth’, which resulted in the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1962.

The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1962 gave all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples the option to enrol and vote in federal elections, although enrolment was not compulsory. Shortly after this, Western Australia and the Northern Territory gave Aboriginal people the right to vote in state elections. Queensland passed an Act in 1965 which finally gave voting rights to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

It was not until 1984 that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were politically equal to other Australians under the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 1983. This Act made enrolling to vote at federal elections compulsory for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Declining Social Cohesion in Australia

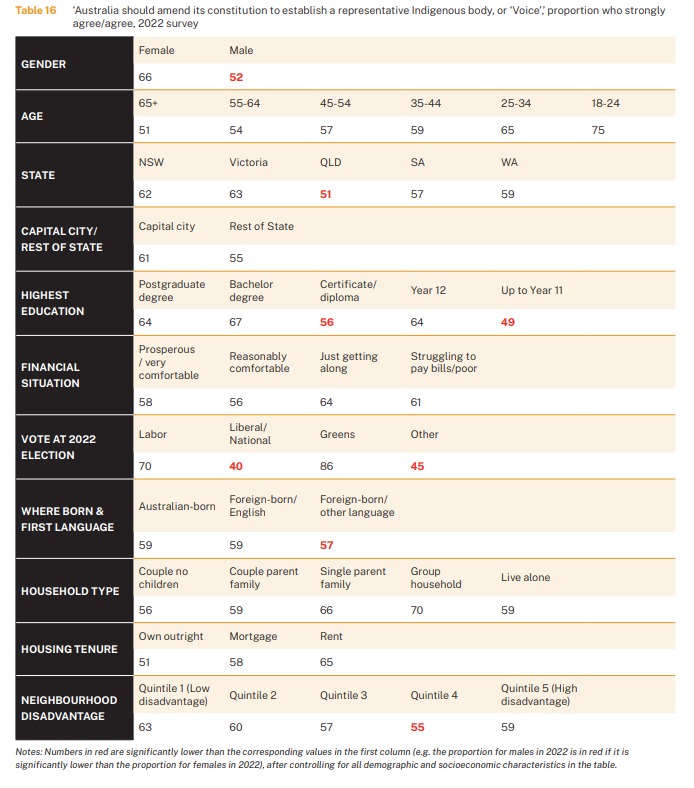

Towards the end of 2022, the Scanlon Institute’s ‘Mapping Social Cohesion’ report indicated that 59% of respondents agreed that ‘Australia should amend its constitution to establish a representative Indigenous body, or ‘Voice’, to advise Parliament on laws and policies affecting Indigenous people.’ At the time of this survey, 1-24 July 2022, agreement was inversely skewed with age, with 75% of 18-24 year olds and 51% of 65+ year olds agreeing with the constitutional change.

The 2022 Social Cohesion report indicated a declining level of social cohesion and financial security, placing pressure against the desire of the population to allow significant change that may have ramifications on what people have.

Even with the age and other segment differences, it was clear from this survey that there was support for the Voice. So, what has changed so dramatically since, with polls generally illustrating a skew towards ‘no’ at tomorrow’s referendum?

The fear of losing what we have now, may be influencing a desire for many Australians not to vote ‘Yes.’ Reducing social cohesion and increasing financial stability due to cost of living pressures is likely playing a role for some not desiring change in the form proposed in the referendum.

There is much debate as to why there has being such division on the Voice, irrespective it does appear that the ‘no’ strategy has had a greater impact in garnering support. They have successfully leveraged fear of change, confusion in many from the lack of clarity and a sense of division. Influencing change is a harder task than fear of the unknown. While the polls may have it wrong, it does appear the Yes campaign got the strategy wrong, or perhaps the odds were stacked too far against to expect anything else.

I still hold hope that the ‘yes’ vote will pull through. Chances are that while much discussion and debate has occurred around the Voice, and progress is ever made, we have seen the best and worst of what it means to be Australians – giving others a fair go and respecting the need to recognise Aboriginal Australians, but also an increase in demonstrations of racism, ignorance and division that likely illustrates that Australia still has a long way to go to making such progress.

— Gough Whitlam 1973